I know I’m supposed to be serious and say some stuff about the arc of this series, but I really want to talk about rarr, Michael Rooker. He was used ridiculously badly in the first season, showing up as Daryl’s older, racister brother, given wholly lame scenery chewing speeches about how racist racist racist he was. Racist. But godamn, the man is Michael fucking Rooker, so I’ve been absolutely gagging for him to show back up. As something other than Daryl’s fever dream. Not that that isn’t hot too.

Though I have read the comic compendium that arcs through the Rickocrats sojourn on the farm and the prison, I haven’t really had a problem separating page from screen until now. So many things were different in the beginning, from Shane’s continued survival to general character shuffling. Which is mostly awesome, except for Lori. Andrea and Michonne fall into the sketchy utopia of the Governor’s town, and it’s pretty neat how softly David Morrissey plays a dude who is obviously going to turn out to be evil. But then maybe I’m just saying that because I’ve read the comix?

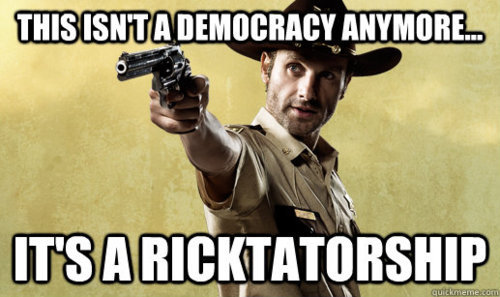

No, no, for sure, any show has to have an antagonist, and there is only one Rick in the Ricktatorship. As close to the edge as Rick is, the Governor’s calm and soft-spokenness reads as a warning. Seriously, folk, screaming your head off might be the right reaction to the zombie apocalypse, and barring that, as it might draw out the walkers, some eye-bugging might be in order. Anyone drinking tea should be watched.

Which brings us back to the spectacular Merle. He was written for shit first season, but he finally makes sense here as a bigger psychopath’s lap-dog – the “hammer” as he’s characterized by a somewhat wobbly-played mad scientist. Splendid Mr. Rooker’s swaggering and Ash-esque brandishing of his stump is neat within a community of larger, fell purpose, where it wasn’t all by its lonesome on a department store roof. Someone like Merle only makes sense in context. Yeeee haw.

Which brings me to Michonne. I have a several page rampage about how her character arc works out in the comix – most of it boiling down to how badly Kirkman writes women, so when he hits the topic of rape, he trips over his own dick and makes a serious mess – but I loved her character so wholeheartedly. Which is another place I’m finding it hard to separate comic from screen, because I’m bringing my love for a page Michonne to the screen, and I’m pretty sure the screen Michonne doesn’t deserve it yet. Yes, she can glower like a boss, and she is clearly a stupendous badass, but I’m not sure that’s enough.

Andrea’s characterization in the town is a little iffy, I think mostly because the writers are holding Michonne back to lend her more mystery or something. So Andrea’s stuck flirting and asking leading questions, because if she didn’t do it, no one would. I invoke Bechtel way more often than I should, but I think that maybe there is a general problem writing women on this show, because when Andrea berates Michonne a little for not knowing her despite their hanging out in the zombie apocalypse for the last seven months, I think, really? That doesn’t make any sense. The Governor’s town is so obviously overlaid with all this manfolk manliness, and Andrea’s openness and Michonne’s closedness feels a little weird.

But whatever. This episode was much more about sketching the Governor, and we’ll probably get our Michonne episode soon enough. And I liked the Governor sketch much more than in the comix, despite some lame dialogue – Andrea again with her “never say never” – because he’s so much less of a cartoon evil, ahem. They’re playing up his likeness to Rick in an almost ham-handed manner – token Asian guy: go kill that dude! token T-Dog looking guy: have no lines! token brown-haired lady: sleep in his bed! – but that’s what I’m really hoping for this season – a real conflict between just barely unsimilar leaders. And I did catch the barely coded “The South Will Rise Again” stuff, screenwriters. Good job.