I finally caught the companion film to South Korea’s Train to Busan, the animated Seoul Station. It wasn’t nearly as affecting as its live action antecedent, but I completely appreciated how Seoul Station went in unexpected directions, and focused on relationships not normally detailed in either zombie movies or, like, regular cinema. This got me thinking about more obscure zombie movies I have known and loved, stuff that either goes straight to video, or only hits a theater or two in LA or New York. Many of these movies hail from other countries and cultures, which lends grist to my pet theory about zombie movies being largely about national character, much more so than other monsters.

The vast majority of zombie movies, high or low budget (but mostly low budget), are produced in the United States. There’s a lot of reasons for this: the US produces many more films, in general, than the rest of the West. Also, the United States (and Pennsylvania more specifically) is where the modern zombie was created in Romero’s game-changer, The Night of the Living Dead. I know there were zombie films before this, but Romero so utterly changed the landscape that they’re as different as chalk and cheese. In the same tradition, yes, but it’s like comparing the ghouls in the 1932 film Vampyr to modern vampires: similar in name only.

The ways zombie fictions ruminate on class, race, consumerism, and the nuclear family was set within an American film tradition, and not always or often in a good way. So much of the long tail of American zombie movies — the sort of thing found in deep dives into “if you like this, then” on your streaming platform of choice — is fucking trash. Americans can’t help but America, cinematically speaking, so the instinct to fascism, spectacle as unearned catharsis, and violence as morality pervades a lot of American zombie movies, regardless of budget. TL;DR: many American zombie movies are Libertarian (if not outright fascist) garbage fires, with a sideline in diseased gender roles. (This is somewhat ironic, given how Romero’s zombie films were always brutal social commentary against exactly that.)

Apocalypses in general are local affairs, once the lights dim and the communication systems blink out. The world narrows to the distance you can travel on foot — at least once the gas runs out, and you leave the car behind — the skyline streaked with the smudges of burning urbanity. But zombie narratives go a step further, reanimating strangers, neighbors, family, and friends in the subtle tweaks and twists of national character gone feral: slow or fast, cunning or mindless, diurnal or nocturnal, contagious or endemic. These monsters show what we become in the 24 hours and three meals from the end of it all.

Warning: possible spoilers in the film descriptions.

USA:

Maggie

What makes Maggie notable in the context of American zombie movies, a film that collects together Arnold Schwarzenegger, Abigail Breslin, and Joely Richardson, is its taunt, Gothic rumination on the parent-child bond. It opens with Arnold traveling into a disease-ravaged LA to collect his daughter, Maggie. She’s infected with a zombie-ish plague, half-dying and half-alive in some overrun city hospital. All the small cues tell you she left because they were estranged — hard to say whether it was the normal estrangement that finds children growing into adults, or a deeper one. When they return home to the family farm, it’s clear it’s both: she’s a normal teenager fed up with her Boomer father, and then also he’s got a new wife and small children who have supplanted her in some ways. I have some autobiographical reasons for why this resonated hard. Anyway.

Maggie muses in a sometimes overly self-serious way about coming home. Maggie, the character, does a retrospective of her adolescent relationships — complete with teen party with a bonfire on the beach — just short years, or long months, after she leaves home. When her step-mom leaves with her half-siblings, it leaves her alone in the house with a dad who can’t even begin to understand, but is turning himself inside out trying. The ways they never quite connect, right up to the bitter end, are shattering, the kind of thing that set me sobbing, an outsized emotional response to what is largely an understated and grayed out emotional landscape. This the best, most finely detailed work Schwarzenegger has put to film in his latter day career.

UK:

The Girl with All the Gifts

When I first learned they changed the race of Miss Justineau, the living teacher of an undead classroom in The Girl with All the Gifts, from black to white, I was worried. In the novel by M.R. Carey (aka Mike Carey, for all you Hellblazer heads), Miss Justineau was black, and the undead child who cleaves to her white. The film reverses this, and it actually works really well, almost better in places. Making Helen Justineau a non-malignant version of the Nice White Lady ministering to children whose humanity is completely denied, and who are black [same/same] says something very different from the reverse, especially with how it shakes out in the end. (And unrelated aside: it’s notable to me how many of the films on this list started life — or undeath muahaha — on the page, and how successful their adaptation. Not everything is World War Z: The Less Said the Better.)

The Girl With All the Gifts is one of a teeny tiny trend of fungalpunk horror, of which maybe the most successful was the Area X trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer. Carey’s story found inspiration in the nightmarish real world story of zombie ants infected by a fungus which drove them to uncharacteristic behavior, after which the fungus would fruit out of their ant heads. The images of ants with fungi protruding from their head carapaces legitimately freaks me out, and I don’t necessarily empathize with insects all that often. The film hews closely to the plot of the novel, a road trippy rumination on a ruined Britain. The girl who plays Melanie is wonderful, playing her smitten child with a sense of resigned sobriety that gives her an out-sized presence. Glenn Close delivers a quietly seething version of the amoral scientist, which is an interesting twist on a trope that tends to oily bombast (e.g. Stanley Tucci in The Core, which is hands down the best version of this ever put to film.) I love both iterations.

Canada:

Ravenous (or Les Affamés)

Sometimes I find the cultural context of specific foreign films so baffling as to render the “meaning” — insofar as that’s a thing — quite opaque. The French-Canadian Les Affamés falls into this category for me, but in a still strangely satisfying kind of way. Much of Ravenous falls into the mode of the zombie road trip, stopping occasionally to eavesdrop on the dead and their inscrutable machinations, or to enact the living’s more visceral conflicts. (And the dead in Les Affamés are truly strange, piling up teetering obelisks of domestic stuff in a clearing in the woods, or here, or there.) There’s this old saw for writers that “dialogue is action” and that almost reductive aphorism maps onto zombie narratives in this weird way. The drama in Ravenous is all in its dialogue and tense standoffs between survivors; the zombie attacks are almost a relief.

Pontypool

The source material for the film Pontypool, Pontypool Changes Everything by Tony Burgess, is both typical and an exemplar of his work. Burgess excels at either elevating pulp to high art, or elevating high art to pulp — because he somehow manages to write deeply philosophical works using absolutely sick imagery, while not prioritizing either. (See also: The Life and Death of Schneider Wrack by Nate Crowley.) This is not an easy thing to do! In fact, I can only think of a couple writers who successfully use the vernacular of both highfalutin literature and pulp styling without denigrating either.

Anyway! Point being: Pontypool is somewhat loosely adapted from the source novel, and in the very best ways. I can’t imagine a film version that somehow cut that impossible middle distance between high and low art that the book does; this will not translate to the screen. Instead the film is a taunt, almost stagy locked-room drama which focuses tight on a couple few characters. Some aspects of the film have become quaint — the whole concept of a “shock jock” has been superseded by media twisted into propaganda by authoritarianism — which takes a little sting out of the proceedings. It’s still an excellent film.

Denmark:

What We Become (or Sorgenfri)

Many of these movies — at least before they are translated into English — have locations in their titles, like the aforementioned Train to Busan. The Danish zombie film Sorgenfri — named after a Copenhagen suburb — was retitled in English What We Become. Sorgenfri means “free of sorrow”, in an almost obnoxious irony, but we will give writers some latitude to be obnoxious when place names are this on-the-nose. I fully expect places like Minneapolis suburb Eden Prairie to become hellish pit stops on the way to apocalypse because come on.

Anyway, What We Become makes full use of its suburban locale, which I don’t necessarily see all that often, Dawn of the Dead notwithstanding. There’s some hot-neighbor-next-door, community-cookout action before the infection locks the suburb down. Each McMansion is swathed with plastic, (almost like in the quick-and-dirty Spanish film series [rec] — more on this later), and if they try to push back against the impersonal authorities in their gas masks and machine guns, quick and brutal violence ensues. If this was an American film, I’d accuse it of 2A essentialism: we need guns to fight teh gumment!!!! But … it’s Danish, so that can’t be what it’s about. Or … not entirely anyway.

Much as Americans like to paint Denmark as some sort of socialist utopia (and don’t get me wrong: America’s fucked), there’s the same cultural, social, and economic stresses like any other part of the EU. I have Danish cousins, and the amount of chauvinism I’ve seen expressed about, say, Turkish immigrants is notable. And that’s not even getting into what they say about straight up Muslims, Turks or no. What We Become taps into a very (white) middle class, very (white) suburban fear of intrusion by the other, and also the fear that the other is already there, hidden within. These kind of insular communities are always predicated on fear: on the other, on themselves — what have you got, I’m afraid of it. In Night of the Living Dead, Romero murdered what should be the romantic survivors, in addition to the nuclear family. What We Become lets some of its characters survive, but only after putting you through some brutal familial self-annihilation.

France:

The Horde (or La Horde)

When I first saw The Horde not much after its 2010 release date, I thought to myself, there is going to be a real and bloody reckoning in France about how the treatment of France’s immigrant population. I knew just a very little about the French attempts to legislate the bodies of Muslim women — for their own good, natch — and it was years before the Charlie Hebdo shootings. But the bloody spectacle on display in The Horde was enough to make me prognosticate doom. Pulp fiction tends to tap into the societal hindbrain, and The Horde was doing that in the goriest, most bloody way possible.

The Horde follows a group of corrupt French police on a vendetta into what reads to me like the projects — low income housing that warehouses the poor and undesirable (same/same). There’s some back story about some drug dealer or whatever killing a cop, but none of this really matters. The fight is between two rival gangs, one of which wears badges and speaks “good French”, and the other have accents and dark skin. There’s a racist old codger (I think maybe even a veteran, but it’s been a while) and a couple other residents to round out the group. The combatants end up trapped in a old apartment building while the horde presses against doors and windows. And of course, several end up bitten, turning at the worst possible moment.

The Horde‘s zombies are faster than Romero zombies, and often a lot fresher, the blood still red and the zombie vigorously intact. As we approach the endgame, one of the cops is given a lovingly detailed last stand, and even more intimate horrific death: standing on the top of a car in a basement parking lot, he shoots and hacks until he’s overwhelmed by hundreds of zombies, and boy howdy do they not pan away. I know this was shot later, but the framing of this sequence reminds me of the season three ender of Game of Thrones, which found Daenerys Targaryen crowd-surfing a horde of anonymous browns. It’s notable to me that the image of a white lady receiving adoration for liberating brown people and a white guy heroically hacking at a mob until he’s overwhelmed are shot virtually identically. I’m sure something like The Pedagogy of the Oppressed has something to say about this, but it’s been some years since my theory-reading days.

The Night Eats the World (or La nuit a dévoré le monde)

The Night Eats the World begins with a musician dude, Sam, coming to his ex-girlfriend’s flat to retrieve some cassette tapes he left after the breakup. The sequence at the party with its byplay and character development between the people marked as protagonist and the inevitably disposable partygoers reminds me of the opening to Cloverfield (and, weirdly, the Netflix series Russian Doll.) Sam crashes out; when he awakes, there’s blood on the walls and everyone is either gone or a zombie.

The Night Eats the World is light on zombie kill thrills, if you’re into that sort of thing, much more focused on Sam’s solitary existence and worsening metal state as he holes up in his ex-girlfriend’s for months. The film manages to find some unexplored corners in the zombie apocalypse: this portrait of fearful loneliness in a teeming city. When I first saw The Night Eats the World, I have to say it didn’t affect me much. My enjoyment was largely intellectual: oh, huh, this is almost a silent film; who even does that? But almost two weeks into my family deciding to shelter in place, the detailing of Sam’s mental state as he rattles around the same couple hundred square feet and considers the death just outside the door: well, this is suddenly, horribly relevant.

Germany:

Rammbock: Berlin Undead

Like The Night Eats the World, Rammbock opens with a dude going to his ex’s apartment to transfer some stuff, and also maybe sorta to rekindle their relationship. She’s not there, but two plumbers are; when a zombie outbreak overtakes the neighborhood, ex-boyfriend and the plumber’s apprentice ride out the zombie apocalypse in the apartment. With other monsters, writers can get a little schematic. This is especially true with vampires. You often see complex list of rules about what a vampire can and cannot do, and then, of course, inevitably how to break those rules. (The most recent Dracula limited series, first from the BBC and now on Netflix, exemplifies this sort of thing.)

Zombies, though, they don’t tend to go this way. The rules are simple: a person dies, they reanimate, then they hunger for the flesh of the living. Oh, I suppose there are some other conditions that may or may not come to bear: does killing the brain kill the zombie? are we all infected or is it contagious through a bite? fast or slow? But these are more set-dressing than, like, necessary for the storytelling. Rammbock‘s zombies, by contrast, are photosensitive, a detail it takes the principles some time to work out. Then when they do, they work towards exploiting this detail in order to save their own lives. Rammock is, again, maybe not the most exciting zombie film ever made, but the location, relationships, and the weird taxonomy of zombies make it worthwhile.

Spain:

[•REC]

This scrappy Spanish found footage horror film was so successful it spawned a movie series and an English language remake (which was retitled as Quarantine.) (The Spanish series has diminishing returns: the second relocates to an airport, which is fine, while the third goes eschatological in a way I did not appreciate at all. Oh, and there’s apparently a fourth I never saw, REC 3: Apocalypse which is by the filmmaker of the first two, but not the third, which is promising. ) REC follows a Bridget Jonesy reporter on a ridealong with some firefighters. They head out to a call in an old apartment building with six or eight units. One of the residents has gone murderously feral; they contain her, but not before one of their number is bit; when they panic-run to the exit it turns out the building’s on some sort of horrible lockdown.

The film ends up being a locked room horror show as various people get infected and infect others. There’s also apparently a plot where it turns out the authorities are evil, but who even cares. It’s obvious they were evil when they locked an entire apartment in to die. Again, this film had certain meanings back when I watched it whenever, but in the middle of a global pandemic, things read a little differently. The willingness to sacrifice first responders stands out, as does the bickering in the doomed apartment building about the motives of those that locked them in. That the outbreak is legible, with known origins and therefore, potentially, a cure is another fun aspect of fiction. It turns out that real life is much more bleak, which is saying something, given the end of REC.

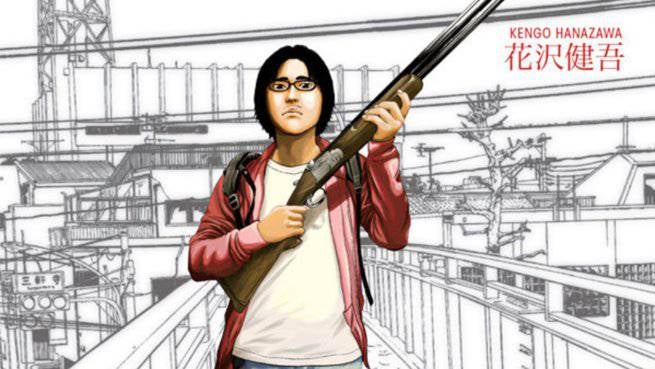

Japan:

One Cut of the Dead

Frankly, One Cut of the Dead is the best godamn zombedy produced since Shaun of the Dead, and in some ways it exceeds Edgar Wright’s most excellent film. Filmed on a budget of $25,000 (JFC), the film relies on what could be a gimmick, but ends up being just a beautifully written script. The first half hour or so of the movie is one continuous take, telling the story of a low budget zombie movie lorded over by a tyrannical director which is then attacked by real zombies. (Not dissimilar in setup to Romero’s 5th outing into his formative zombieverse, Diary of the Dead, but that reads pretty Boomer-y these days.) After this impressive feat of film-making is a crazy bananas twist that had me all-capsing to my viewing partner, the indomitable sj, for at least the next half hour. It’s just … the whole thing is so well done it makes me tear up a little.

The trouble with talking about One Cut of the Dead is the several spoilers in serial that happen in the second act. All that aside, I can say that the shifts in tone in One Cut are masterful, running from comedy to terror and back again without even a blink.