Many moons ago, my good friend Joanna was living just over Grand Ave from me in a nice little brick fourplex. The back yard had this incredible shrub rose, one that no doubt had been planted in the 20s, and was now seeking total yard domination. The landlords decided to rip it out, because they were jerks. Under it was a rhubarb plant, a plant that had managed to thrive under a rapacious rose for a hundred years, and also had an eye towards world domination itself. I got a call from Joanna: you have to come save this rhubarb! You’re the only person I know with a yard! I duly went over with garbage bags and a spade, and planted the poor thing back by the garbage cans. It doddled on for a couple of years until I built a box for it and moved it, at which point it went completely nuts. It flowered this year, which allowed me to cut the scariest bouquet ever.

I’m gonna lay eggs in your thorax

The house I grew up in in South Minneapolis had a similar rhubarb plant, this big, almost black-leafed thing that Mum would occasionally cut stalks from to cook up into sauce that we ate over vanilla ice cream. I don’t remember one at Grandma Dory’s house, but I’m sure it was there somewhere, all of her pies and bars – always bars, in the 70s, never cookies. I used to filch the sugar bowl off the table and go out and eat stalks straight off the plant, dipped in sugar, the sour of the plant almost painful in that way that makes your eyelids flutter, and then the crystalline melt of the sugar. I absolutely love the shit out of rhubarb. I wrote Grandma Dory a letter once the plant got going; do you have any recipes for me? She responded by mailing me Rhubarb renaissance: A cookbook, publication date 1978, which is filled with her terse marginalia – “good” or “delicious” or, harder to parse, a + – and includes three yellowed newsprint squares pasted into the back leaf of recipes she clipped from the paper.

Rhubarb renaissance: A cookbook is completely a product of its time, heavy on the sugar, specifying margarine for everything. (My rule is to halve the sugar in cookbooks from the 70s, and add more if it’s too sour. You can’t take it back out again.) There are lots of bars, and pork, and, adorably, a biggish section on punches. Why don’t we make punch anymore?! Observe:

Mock Pink Champagne

Rhubarb juice – 1 cup sweetened and chilled

Dry white wine – 2 cups, chilled

Ginger ale – 1 quart bottle, chilled.

For each glass, use four tablespoons rhubarb juice, stirred well into 1/4 cup wine. Fill glass with ginger ale.

Isn’t that adorable??? There’s something called a California Waker-Upper that includes prune juice and powdered milkand I just…I’m not even sure I have words. There are a bunch of beet recipes too which are all very good, really pretty and rosy in addition to being good pairings taste wise.

Anyway, the real thing I learned from this book is how to cut rhubarb for sauce or pie. I’d always just chopped the stalks lengthwise and then dumped them into the pan, with a little bit of water. Wrong. It goes stringy, as you might know, and holds its shape in a way that isn’t awesome. Also, adding water makes it too soupy. You have to split the stalks down the middle, and then again if they’re big enough, and then chop them. Then leave the chopped rhubarb for a half hour, and the stalks will weep the liquid you need to cook them, no water necessary. Adding sugar hastens the process. Well watered rhubarb won’t need any water added, and, probably a tablespoon or three of minute tapioca wouldn’t hurt to add to the mix to make it thicken (especially with pie.)

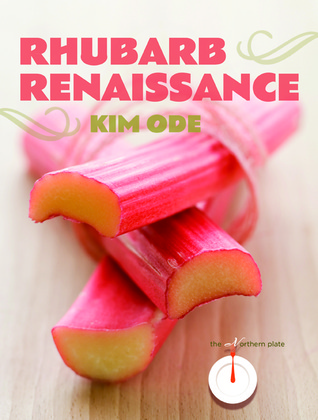

So then, many moons later, my husband gave me Rhubarb Renaissance as a birthday gift. Oh, I already have this! I said, and then pulled down the recipe book from Grandma Dory. Nope. Apparently rhubarb goes with renaissance in the titling world, and, as far as I can tell, Ann Saling and Kim Ode have no connection, nor do their cookbooks. Kim Ode writes for the local paper, and, judging from the beautifully vernacular recipe for rhubarb wine in the back that was written by a grandmother, is a Midwesterner born and raised. Both books talk about how rhubarb originates in Asia, and then migrated over to Europe, mostly as an herbal remedy and not as, you know, food, until the Scandinavians got ahold of it and enough sugar to start making pie. Which is how come rhubarb is still a sort of Midwestern, flyover state kind of plant. My Scandihoovian people, when they were getting tricked by the railroads to come to America, brought the plant with them. And here we are! Ta da!

Kim Ode’s renaissance focuses on the savory applications of the pie plant almost exclusively, a corrective to rhubarb’s long, staid marriage to the strawberry. I know several people – two cousins and the aforementioned Joanna – who are at war with this pairing. All rhubarb or nothing in pies! I ran a berry experiment one summer, pairing rhubarb with every berry I could think of other than the straw in pie, and blueberry-rhubarb is the most interesting, while rasp+rhu is probably the most crowd-pleasingly sweet. I have yet to try mulberries, but my crazy neighbors’ shrub is going gangbusters, so I might steal a pint and see what happens. Anything to keep the berries out of the birds, who then deposit livid mulberry crap all over my porch. Jerks.

Ode’s book has a lot of fish – shrimp in particular – and a whole lotta chutneys. My only complaint is much of the book is foodie fussy, with a fair number of items that if you’re in, say, Grand Marais, Minnesota might be hard to source. I’m lame enough that even if I were in town, I’m not sure I’d know where to get parchment paper for packets, but that could certainly be chalked up to it’s not you, it’s me. And I mentioned this before, but the rhubarb wine recipe, which is dodgy and personal and hard to follow the way family lore is dodgy and personal and hard to follow, is absolutely worth the price of admission for me. Recipes are notes to self, a quick notation of “good” or “cut these ingredients”, because you know how to think like yourself when you go to perform a familiar but half-forgotten task. “Test for sweetness and add sugar,” you say, cryptically, but you know what you meant. “+” you said, and you know what that meant too, but maybe your granddaughter didn’t. She’ll just have to cook until it comes clear.