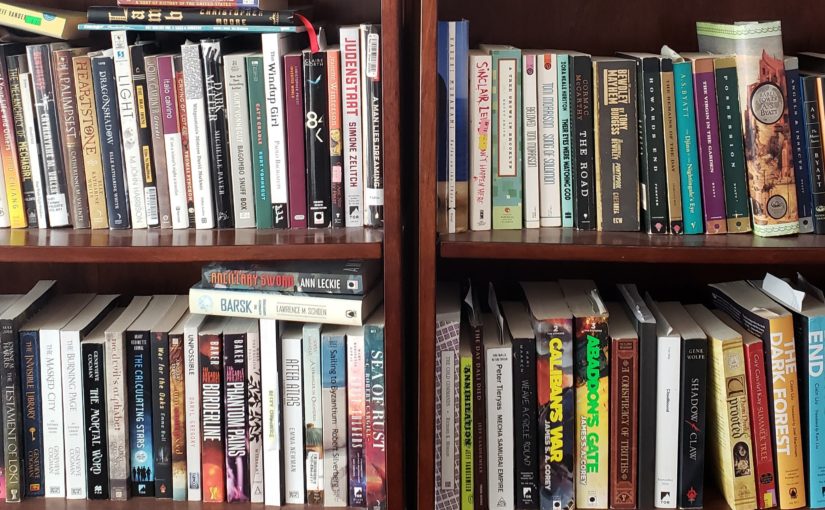

I’ve been doing these year-end roundups of my reading for a couple-few years now. It’s always illuminating to see what my aggregate choices are because it’s not like I have a plan starting in January. I’ve largely stopped writing reviews beyond the tossed off observation nor do I get much in the way of ARCs anymore, so this is me left to my devices. I feel like I’m still kinda coming out of my pandemic slump when I couldn’t read anything but historical romance or real light fantasy. Apparently I’m now deep in the rompy space opera phase of my years long depressive episode. I’m still reading a fair amount of fantasy, urban or otherwise, but the regressive politics of a lot of historical romance have put me off the genre for now. There are exceptions, but I’m sticking with well-vetted authors for the time being.

Zombies

Obviously I’m a nutbar about zombies, and I presume every year I’m going to have a half dozen or more zombie novels on the list. I did Zombruary, as usual, but then worked my way through the bonus books as the year went on. We’re well past the zombie heyday of 10-15 years ago, so in general the stuff being published now tends to be odd and oblique, coming at the metaphor of the undead in unusual ways. There’s some zombie books I read this year that were published earlier, when zombies tended to be more Romero-style shamblers, but it was the more recent narratives which strayed from that style that I found satisfying.

Domino Falls by Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes. I read the first in this series, Devil’s Wake, last Zombruary, and really enjoyed it. It’s YA with a diverse cast of characters road-tripping through the zombie apocalypse. They have the opportunity to stop running for a bit when they’re taken in by Domino Falls, a seemingly zombie-free town. The little bit of safety and normalcy they experience there is such a temptation, because it’s obvious there’s something completely sus about the compound out of town run by an L. Ron Hubbard-y cult leader. Domino Falls doesn’t reinvent the wheel or anything, but the revelations about the source of the zombie plague are surprising. I will die mad that no one saw fit to publish the third book in this trilogy.

Silent City by Sarah Davis-Goff. I also read the previous book, Last Ones Left Alive, last Zombruary. Silent City takes place 6 years later. The main character (and narrator), Orpen, is now about 20, living in the titular silent city — which used to be a neighborhood in Dublin — and working as a Banshee, a fighter in an all-female paramilitary group. There aren’t many post-apocalyptic stories which take place decades after the cataclysm, and the slow pan of modernity being swallowed by relentless nature was very powerful — the sequence in the airport was gorgeous. Orpen continues to be kind of a stick, but I like that the damage in her narration is caused by naivete more than anything.

Eat Your Heart Out by Kelly deVos. My complaints: too many point of view characters with same sounding voices and a strangely plausible but squishy ending (especially given the swerve into somewhat pulpy territory in the second act.) Otherwise this YA novel is a delight: snarling, funny, and occasionally poignant with a plot that positively zips. The set-up is wonderfully subversive: a bunch of kids at a fat camp have to fight a zombie outbreak. Eat Your Heart Out is absolutely furious about how much bullshit fat kids — and especially girls — have to endure. While there is a somewhat didactic message to the novel, it never sacrifices forward momentum and harrowing sequences for the cause.

A Questionable Shape by Bennett Sims. I think one’s enjoyment of this musing literary take on zombies hinges on how much daylight you think there is between the main character and the author. Like if Sims thinks, yeah, this dude is amazing and insightful, that’s all insufferable. But I don’t think he does, and therefore A Questionable Shape is something like a satire, but not as aggressive. There’s def a DFW philosophy major vibe to the proceedings, complete with endnotes, though — and this me being kinda bitchy — DFW is significantly funnier.

I do think it’s notable — again — how accurately zombie fiction written before the pandemic captures the pandemic. Sims captures the worry and interpersonal conflict of people in lockdown so well, and I feel like this is the most naturalistic zombie outbreak I’ve ever read: there’s not a lot of arm-wheeling and violence, more wearing, anxious boredom cut with strange pleasures. One of my strongest memories of lockdown, for example, was driving to work in an empty downtown, cresting the hill and watching the sun rise over the water, and the feeling of both wonder and desolation. Just like that.

Grievers by adrienne maree brown. Probably unsurprising that something called Grievers ended up being intensely sad, but I was still both filled and emptied by how sorrowful this novel ended up being. Dune’s mother one day just stops in place, standing over the sink. Dune takes her to the hospital where they declare her catatonic but not in a coma, with the implication that she’s kinda putting it on. Dune takes her home, where she withers and dies. A week later there’s a knock on the door: Dune’s mother was patient zero for an unknown illness, and all over Detroit, people just stop. The illness only affects Black people, and the novel follows Dune through Detroit’s accelerated emptying while she grieves her mother, her family, and the city itself.

I believe it would be customary at this point to call Grievers “a love letter to Detroit”, which is as true as any such facile observation goes. But it felt to me more like the visitations I went to as a child, with the dead on display while the garrulous and sometimes fractious family carries on living, peeking into the casket to remark on the states of the body. Grief often feels like anger, just as fury sometimes results in tears. Grievers is sad, yes, but it’s also furious and hopeful and resigned and guilt-ridden, all bound together like the bones of Dune’s mother, cremated in her own back yard by her daughter. Amen.

Roadtrip Z series by Lilith Saintcrow (Cotton Crossing, In the Ruins, Pocalypse Road, and Atlanta Bound.) Saintcrow is one of those journeyman writers I’ve noticed but never read, and this was the year to give her a try. I started with The Demon’s Librarian, which I didn’t like: Felt like a tent pole for a series that never got written. The mythology is both over-complicated and under-explained, but the thing I really disliked was the constant rapey thoughts of our ostensible love interest, a weird choice for an otherwise quite chaste novel. I figured I’d give her one more go with the Roadtrip Z series, because zombies.

Roadtrip Z must have been published during that minute when everyone was serializing everything, so each book is more installment than coherent narrative. As such, the books feel padded at times, drawing out the proceedings with same-y seemingly zombie attacks and scavenging. (This is a common feature of serialized fiction, like, you know, Dickens. Though replace zombies with Victorian capitalists. Same/same.) But the padding affords a more languorous journey to and through the actual zombie apocalypse, which gives room to Saintcrow to write some hella character studies of more minor characters. But occasionally her hero still seems like a panty-sniffer? He does improve as the series goes on, for sure. Anyway, totally cromulent insomnia read for me.

Death Among the Undead by Masahiro Imamura. Death Among the Undead enlivens the shin honkaku genre by adding zombies to the mix, wocka wocka. The set up is thus: a bunch of college-aged sex pests and the women they prey on go on a retreat in the country. This same group of sex pests did this retreat the year before, and clearly messed up the women on that retreat so bad that there was at least one suicide. Zombies attack; the group gets trapped in the dormitory; someone starts picking off the sex pests in impossible locked room scenarios. All of that is delightful, of course, but I’m just not much of a mystery reader, and this is a mystery first and foremost. Like it seemed insane to me that everyone was standing around playing talking dog detective when there were FUCKING ZOMBIES OUTSIDE what is wrong with you. Anyway, not to be a drag. If you like clever locked room mysteries, this is a fun little novelty, but that’s ultimately all it is.

Revival, Vol. 1: You’re Among Friends by Tim Seeley, et al. I don’t think I ever finished out this comic series because I have a bad habit of wandering off midway through a series, so I thought I’d have another go at it. In the town of Wausau, Wisconsin, all the people who died on one specific day get back up. They’re not classical zombies — shambling, decomposing killers — but they’re still occasionally uncanny and the whole situation disturbing. The town is quarantined and then the real fun begins. I absolutely adore the whole Midwestern Noir vibe of this series. Super good.

It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over by Anne de Marcken. For a genre that often includes the sudden, violent end of a person’s loved ones, zombie stories often don’t address grief all that well. I can think of a couple. The aforementioned Grievers, fittingly, is suffused with sadness, while Zone One by Colson Whitehead considers loss through the eyes of a depressive, which is its own kind of sorrow. Though it is lightly, carefully touched, grief is the burnt frozen center of It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over, the kind of thing seen out of the corner of the eye and in confusing circumlocutions, as the very language breaks down. What even are you talking about? The zombie’s hunger, its sense of cold emptiness, can work a wonder as a metaphor for the hard shocking losses that find you putting one foot in front of the other, watching from outside yourself as you continue on. There you go, you think, but you’re still sitting right here.

The Undertaking of Hart and Mercy by Megan Bannen. Not quite fair to tag this as a zombie novel, because while there are undead, the story is more an epistolary enemies-to-lovers set in a truly strange fantasy land. The setting is this odd mix of modern — like there are phones and something like cars — and magical, with a central religion that is just neat. Mercy, who works as an undertaker in the family business falls into a courtship by letters with Hart, who is something like a forest ranger, if instead of trees there are zombies. I thought the opening was rough — Bannen doesn’t handhold too much, which I appreciate, but then the world is very weird and I could have used a little more explanation — but! it tightens up considerably in the second half. I was really into it by the end, which is great, because I just figured out this is the first of a series. Would read more in a second.

Space Opera

I haven’t been super into space opera because so much of the early stuff is, what, often imperialistic in ways I find unpleasant? Especially the books that lean more military sf — those stories can get downright jingoistic. But I feel like there’s been a lot of writers taking the societal microcosm of the space ship and doing some cool shit with that. Like Rivers Solomon in An Unkindness of Ghosts addressed chattel slavery on a generation ship, beautifully, awfully. In the other direction, Becky Chambers’s Wayfayers series is shot through with an ordinary sort of kindness in extraordinary circumstances. (Honestly, sometimes ordinary kindness feels extraordinary, especially given the current political climate.) Anyway, so I read a lot of rompy space opera this year.

Only Hard Problems by Jennifer Estep. I read the previous two in this series, Only Bad Options and Only Good Enemies, last year. They’re the kind of books in which there are things that drive me straight up a wall — the world-building ranges from clumsy to downright convenient, and the in-world neologisms hurt my feelings — but they have a pulp energy I really dig. (I’m not so much of an asshole I’ll hate-read an entire series, so know that if I say something annoys me in a series I’m still reading, I mean it affectionately.) They also feature a sort of science fictional mate bond which is depicted as mostly a nightmare, and I love when writers go after that trope. (This will become a theme in my reading.) Only Hard Problems wasn’t that great though: It’s a novella acting as a bridge to the next novel, which is fine, but I’m almost always better off reading this sort thing after I read the next novel. (This will become another theme.) Oh well.

Finder by Suzanne Palmer. I feel like fans of the Expanse series by James S.A. Corey might enjoy this. It has a similar, if smaller, vibe, maybe with a little early William Gibson thrown in. Furiously paced space adventure that leans into the gee whiz tech while still being pretty grubby. Our main character is the ridiculously named Fergus Ferguson, who comes to a backwater community to steal a space yacht back from a local gangster. The locality is made up of variously sized space junk and habs, and many of the smaller communities are actively at each other’s throats. Fergus’s interventions end up upsetting the balance, and everything goes spectacularly to hell. There’s weird (and terrifying) aliens, jury-rigged IEDs made of sex toys, crawling through Jeffries tubes, space roaches, Saudukar-like religions, and so much more.

Calamity and Fiasco by Constance Fay. I wasn’t over-wowed by Calamity or anything — the main character is a little bit of a boo-hoo rich girl — but it’s the kind of story that has a secret underground weapon in a volcano, and the main characters are delighted to keep saying “volcano-weapon base,” lol. I really appreciated the way world-building worked as foreshadowing in Fiasco, which isn’t as easy as it looks. Plus the world was just cool, with a floating city circumnavigating a planet. Real care was put into how the inhabitants of such a place would interact with their environment. I’m also very amused by Fay’s invented insult “priap” which obv comes from the Greek god Priapus, who was a fertility god known for his huge dong. Lol, nice.

Warrior’s Apprentice by Lois McMaster Bujold. I read the Cordelia books in the Vorkosigan series (Shards of Honor and Barrayar) absolutely ages ago and totally dug them (hat tip to my friend Elizabeth for turning me onto them) and then never read on because I have a problem wandering off. This spring when I went to a local con, I had the opportunity to have dinner with Bujold (I’m brutally name-dropping here; there were like eight of us at dinner) and she was lovely, so I finally started the Miles books. This is a lot of fun! Miles is a precocious but disabled rich kid who manages the most incredible mix of falling upwards and getting in his own way. Bujold also does the thing where she lulls the reader into the sheer fun of the goings on, and then casually rips your fucking heart out.

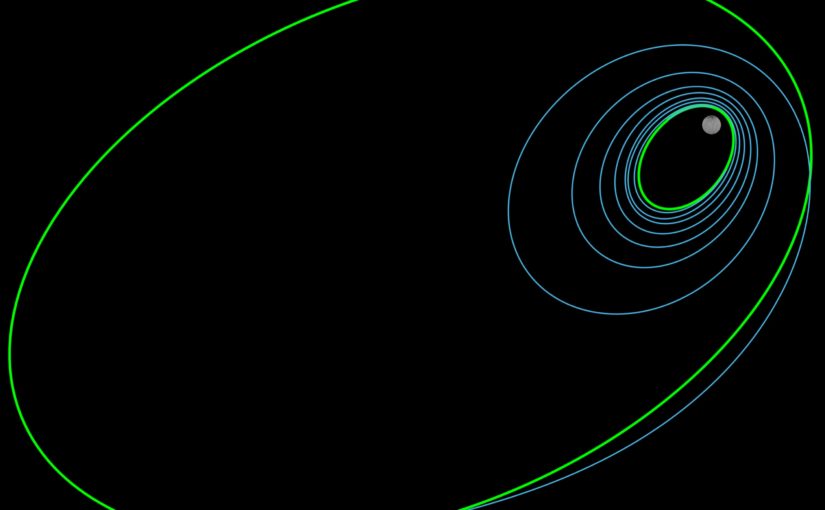

Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson. Red Mars follows the first 100 colonists to Mars, starting from the 2 year space journey to Mars up to the original 100 being almost overwhelmed by the colonizing Earthlings. I feel like KSR generally does an excellent job of mixing hard science with actual characterization, and while that’s generally true here, I did occasionally get a little antsy with the science stuff slash descriptions of landscape. Which is funny, because I don’t think the novel would be better at all if that was redacted. It is important that we get a real sense of the scope, scale, and difficulty of colonizing Mars. I think my problem might have been listening to the audio during the commute, which doesn’t do much for leisurely descriptions of the Martian landscape spooling past.

Steal the Stars by Ann Aguirre and P.T. Maylee. Sorry to say I actively hated this, because I really, really like Aguirre. I dig her books because while they’re not showy, her novels are well constructed and often quietly subversive. And this is a harder thing to put my finger on, but I get the impression she really enjoys writing? Like there’s a joy under her prose? Obvs most writers do it because they love it, so I’m not sure what I’m trying to get at, but there is a sort of enthusiasm that feels very soothing to me. Alas, I found Steal the Stars clumsily written with a whole raft of characters I found annoying. I will not be continuing this series.

Full Speed to a Crash Landing by Beth Revis. This one is kind of a redemption arc for me like Road Trip Z, because I didn’t like the first Revis book I read ages ago called Across the Universe. (It hit too many of my pet peeves, which isn’t necessarily its fault.) I loved Full Speed to a Crash Landing. While the setup is something you can find in just scads of space fiction — loner captain wiseass decides to work with potentially terrible colonial-space-fleet types to do space fuckery — I thought the main character was just great. So many of these loner captain types are eaten up with their tragic backstory. While Ada Lamarr may have a tragic backstory, she’s not going to let that get in the way of being awesome. Also, and this may be a spoiler, it turns out the whole thing was a heist, and I fucking love space heists.

Michelle Diener gets her own line item because I read a lot of her stuff.

Class 5 series by Michelle Diener. I finished off last year reading the absolute shit out of Diener’s Class 5 series. They’re not particularly inventive — the aliens all have a single defining trait, and the universe is Star Trek lite — but I found them so compulsively readable. The kind where you’re like, just one more chapter, and then curse yourself the next day for staying up until 2am reading. The sixth book in the series, Collision Course, came out just a couple months ago, and when I went to read it, I realized there was some stuff that tied back to a novella I’d never read, Dark Ambitions. So I went back and read that. It was fine, but like Only Hard Problems, I probably could have skipped it. In Collision Course, Diener moves away from the standard plot of the first books — abducted Earth woman makes friends with a potentially evil AI, a plot which was frankly getting tired — to good ends. Also, there’s a believably pregnant woman as the protagonist, which you never see.

Verdant String series by Michelle Diener. I began this year by reading the absolute shit out of Diener’s Verdant String series: Interference & Insurgency, Breakaway, Breakeven, Trailblazer, High Flyer, Wave Rider Peacemaker, and Enthraller. I didn’t vibe on this series as much as Class 5 at first. The characters are very similar to the ones in Class 5 — Diener excels at a certain kind of competent but not overpowered woman who doesn’t spend too much time either self-indulgently crying about her tragic past or preening about how she’s not like other girls — but the series isn’t as space opera-y, tbh. The titular breakaway planets are corporate-controlled hellscapes outside the jurisdiction of planets ruled by, like, representative democracy or whatnot, which I can dig because I get to froth at the mouth about capitalism. They do steadily get more intense as the evolving plot going on the background of each largely standalone installment ramps up. I think my favorite is Wave Rider, which made me literally gasp out loud when one of the assholes trying to kill our heroes took a shot at some alien whales. That’s the kind of sentence that will indicate to you whether you’ll like this as well.

I also read The Turncoat King and Sky Raiders by Diener, both of which are the first book in their respective series. The Turncoat King isn’t even space opera; it’s more generic high fantasy than generic science fiction. I thought a magical system based on traditional women’s work — needlepoint, in this case — was interesting, but everything else was kind of blah. Not bad, but also not great. Sky Raiders depicts a clash of high- and low-tech cultures, with a little bit of indistinguishable-from-magic thrown in. Basically space-faring aliens have been abducting people from a world with Renaissance-level technology. The whole set up has similar vibes to The Fall of Il-Rien series by Martha Wells which I read last year and really enjoyed, but, and I don’t mean this meanly, The Fall of Il-Rien is significantly cooler.

Various Series…es that I Started/Continued/Finished/Reread

I always have dozens of series that I’ve started and never completed, meant to get back to, whatever. Then there’s the series that are still being published, which I occasionally have enough forethought to keep up with. I’ll also revisit stuff when I feel bad for a comfort read. So this will be that.

The Earthsea Cycle by Ursula K Leguin. Y’all know my thoughts about Le Guin, so you can imagine how satisfying it’s been to revisit a series that has etched itself in my bones. Last year I reread the first two Earthsea novels, A Wizard of Earthsea and The Tombs of Atuan. Those two novels almost function as a dialectic between traditional concepts of gender: A Wizard of Earthsea is a classic hero’s journey about a gifted but arrogant young man; The Tombs of Atuan is that, but in reverse, so it’s not like that at all. The thing I love so much about Le Guin is how she can so perfectly express something, but then come back to that expression over and over, in ways that find that expression changed, and both the origin and the change can be true.

So I read the next three Earthsea books — The Farthest Shore, Tehanu, and Tales from Earthsea — which were an interesting mix. I didn’t groove on The Farthest Shore as much as I remembered. The antagonist felt remote, and the divine right of kings messaging felt a little off, given Le Guin’s oeuvre. Tehanu is still the absolute banger I remember it being, and possibly more so. I think it’s the kind of book one appreciates as one gets older, which is the neatest thing to find in a series that started life as young adult novels. I wasn’t that into Tales From Earthsea when I read it first, but it’s grown on me, especially given the excellent afterword that I don’t think I’ve read before. This year I’ll finish up with The Other Wind for sure.

The Grief of Stones by Katherine Addison. The Grief of Stones is a direct sequel to The Witness for the Dead, which I read last year, and shares a world with The Goblin Emperor, which I read long enough ago that I’m not sure what the connections are. I’ve enjoyed this series so far: it has an attention to bureaucracy that I love, and is a procedural with something like a psychic coroner as the lead. The real thing I love is that the main character is a nuclear hot mess — like white hot — but he’s also super competent in a quiet, unflashy way. Or I guess that happens a lot in detective fiction, but he’s also not an abusive addict slash dickhead and his hot-mess-ness is grief-based more than anything, which is much more rare. I also love the slow burn thing with that one guy. Like I’ve been in this world long enough that when that one person switches from the formal you to the personal one, I gasped.

Psy-Changeling by Nalini Singh. I will forever be on my Psy-Changeling bullshit. Forever. So this year I reread both Heart of Obsidian and Shards of Hope. Heart of Obsidian is easily my favorite of the whole series. Singh is always good at writing lovers recovering from serious childhood trauma — the Psy are a people traumatized on racial and generational levels — but it’s especially well done here. Rereading Shards of Hope, which I also dug for its suspense/thriller stylins, ended up being fortuitous. That’s where we’re first introduced to the characters in Primal Mirror, the most recent novel in the series, which I also read this year. I did not dig Primal Mirror. Even though the degradation of the PsyNet is accelerating and its collapse imminent — which would effectively genocide the Psy race — the events of Primal Mirror feel remote and disconnected. Which lead me to believe that there was going to be some 11th hour nonsense pulled out of thin air, which duly happened. I tend to find Changeling alphas insufferable, and while our romantic hero Remi Denier isn’t near the worst (*cough* Lucas Hunter *cough*) he still is what he is, which is utterly basic.

The Rivers of London by Ben Aaronovitch. I continued this series largely on my commute on audio. The reader for the series, Kobna Holdbrook-Smith is just stupid good, with a facility for the fine gradations of the accents in the British Isles. I am also here for the architecture porn. I finished three novels — Whispers Underground, Broken Homes and Foxglove Summer — in addition to a novella — What Abigail Did That Summer — which takes place concurrent to Foxglove Summer. Whispers Underground is the third in the series, and still a romp for the most part. It’s at the end of Broken Homes — which features so much brutalist architecture <3 — when shit really goes pear-shaped. Aaronovitch retreats to the country in Foxglove Summer which I was initially apprehensive of: the stories heretofore were so embedded in London that I didn’t know if decamping to Surrey was going to work. It did, often because of murderous unicorns, but I am looking forward to getting back to London. What Abigail Did is another interstitial novella, and switches protagonists to the main guy’s cousin, Abigail, which I both was and wasn’t into. I thought she was often funny in the way kids are funny about the olds, but then sometimes the boomer behind the character shone through. But I do love a carnivorous house, so.

Crowbones by Anne Bishop. If you’ve read much Bishop, you know how infuriating her books can be: when she’s good, she’s good, and when she’s bad, nngggghhh, and you never know which you’re going to get. Written in Red, for example, takes a stock Bishop character — the gormless ingenue whose helplessness inspires devotion — and makes her work so well you don’t even notice how fucking annoying that kind of character is. Furthermore, the world of The Others (which both Written in Red and Crowbones take place in) is the kind of alternate present that I groove on: recognizably modern, but with a large scale disordering element, like the introduction of magic or something similar. (Sunshine by Robin McKinley is a good example.) But sometimes Bishop’s bad habits and writing tics overwhelm everything, and you end up with Crowbones, a novel in which everyone’s motivations are so stupid it’s insulting. She’s also got it out so hard for academics it makes me wonder if a PhD candidate killed her dog or something. I would normally chuck something like this pretty quickly, but I kept hoping it would improve like the previous Others book, Wild Country, which also started out annoying to me, but then improved drastically as it went on. Alas.

Bitter Waters by Vivian Shaw. I have enjoyed the other Greta Helsing books, and I’m still looking forward to the newest installment coming out this year, Strange New World, but this novella feels inert and inessential. (My dissatisfaction with sidequel novellas has been such a theme this year I will probably stop reading them going forward, something I only figured out writing this list.) The Greta Helsing books are about a descendant of Dracula‘s van Helsing acting as a doctor for the supernatural instead of hunting them. This story kicks off with a newly turned child vampire coming under Greta’s care, a child who was turned against her will in what feels like a coded sexual assault. But then much of the focus of the novella was on Ruthven’s emotional crisis. Honestly, I didn’t get why he was having a crisis in the first place, because it wasn’t about what happened to that child, and immortal children are like the worst thing I can think of (e.g. Claudia et al.). Fine but not great.

Subtle Blood by K.J. Charles. It had been a hot minute since I read the first two books in the Will Darling trilogy set in post-WWI Britain, so I was occasionally a little confused by the overarching plot, but it wasn’t a problem in the end. We get an up close view of Will’s lover, Kim’s horrific family, as the mystery plot concerns Kim’s brother, the heir apparent, being charged with a murder he all too plausibly could have committed. The real meat of the story is Will coming to terms with what the war did to his emotional capacity: Kim quite desperately needs Will to make their relationship a bit more than unspoken, while Will had the ability to plan for the future knocked out of him in the trenches. The last of the Will Darling novels pretty much sticks the landing.

The Liz Danger series by Jennifer Crusie & Bob Mayer. I listened to all three Liz Danger novels — Lavender’s Blue, Rest in Pink and One in Vermilion — on the commute, and they were perfect for it. Crusie is one of the few people who writes contemporary romance that doesn’t make me break out in hives, and Mayer (apparently) writes military thrillers. (I’ve never read his stuff.) Together, they are magic. The series follows one Liz Danger, who breaks down outside of the shitty small town in Ohio she escaped from 15 years previous, and then gets sucked right back into all that bullshit. Even though there’s a lot of quipping, borderline absurdity, and hijinks, there is some deep shit going on under the surface. Like Liz’s mom has collected close to 400 teddy bears, and though dealing with the bears is a funny motif, Liz’s mom is actually awful. When Liz finally confronts her, I felt the terrifying rush of that in my bones. Plus there’s a crooked land deal, and I love a crooked land deal. (As my Dad would note: you don’t have to say crooked.)

His Majesty’s Dragon by Naomi Novik. This series has been on my list for a long time because I find the idea of Napoleonic Wars + dragons to be delightful, but it took me a while to get into this. The main character, Capt Laurence, is a total stick, and I got sick of how prissy he was through the first two thirds. But he has a couple humbling experiences and loosens up considerably as the novel progresses. His dragon, Temeraire, with whom he bonds in a way reminiscent of the mechanic in Dragonflight, is the freaking best, and I love how he constantly challenges or punctures Lawrence’s (and Georgian England’s) dumb ideas. While I think the middle drags a little, with Temeraire and Laurence grinding and leveling up, the final dragon battles are thrilling as hell.

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer. Per usual, Vandermeer is a godamn master wordsmith. In the first novella — Absolution is three novellas stacked in a trenchcoat — I kept having to go back and reread sentences because there’s something subtly and persistently off about where they end up. It’s not a mistake or bad grammar or something, but deliberate weirdness that enhances the more overt weirdness of the situation. (I read this with two other people, and they had this experience too, so I wasn’t just tired/menopausal. Plus, I could not read this anywhere near bedtime, lest the screaming fantods infect my dreams.) I enjoyed the first and last section better than the middle, which I thought dragged a little. And this is on me, but while I’d listened to the entire Southern Reach trilogy not that long ago, the details had drifted enough that I was occasionally at sea as to the import of various events. I strongly recommend brushing up on anything that intersects with Lowry and Whitby, and you’ll get more out of Absolution.

Historical Romance I Could Handle

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve had a hard time with historical romance recently. So mostly what I read was books in a series I was already following.

The Earl Who Isn’t by Courtney Milan. Enjoyable conclusion to the Wedgeford Trials series, about a small town in Victorian England people by a significant population of Asian ex-pats. While I liked the main couple and all, Milan really excels at writing complicated relationships between parents and their adult children. Nice asexual rep, if you’re into that sort of thing.

The Beast Takes a Bride by Julie Anne Long. The Beast Takes a Bride catches up with a couple five years after their estrangement, a break which happened on their wedding day. The story moves forward and backward in time quite adroitly, uncovering the initial conflict and working towards rapprochement at the same time. I continue to love the found family themes in The Palace of Rogues series, as well as the space given to minor characters to have their own lives and interests, irrespective of the romantic plot. We get to attend a donkey race in this novel, for example, something alluded to as a most beloved pastime of the often crass and flatulent Mr Delacourt. As usual, Long’s prose is top shelf stuff. She knows how to build a theme and just slay you with a tiny, careful observation. (I also reread Beauty and the Spy which was a little overstuffed as the first in a series, but still enjoyable.)

Riffs, Updates, & Intertexts

A number of the books I read this year were based on or heavily alluded to a classic. These are they.

Exit Ghost by Jennifer R Donohue. Gender-flipped contemporary Hamlet that leans hard into the witchery underneath the play. Juliet Duncan was almost killed by a ricochet when her dad was assassinated. Six months later she gets out of the coma, and promptly performs a ritual to call her dad’s ghost, in an altogether badass version of the battlement scene. While not narrated by Jules, the story is a close third person, and the effects of her traumatic brain injury make events feel strange and wiggling sometimes, in addition to all the witchery. Very similar vibes to Scapegracers by H.A. Clarke, which I read last year and highly recommend — the magic, the queerness, the scrabbling youth — but an older iteration: maybe just out of college (or that age), and competent enough to be fucking dangerous. Really good.

Ghosted by Amanda Quain. Well-considered modern take of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, one which doesn’t aim to capture Austen’s winsome comedy of manners and affectionate satire, but instead mines the source material for themes not explored in text. To wit: the haunting of grief, and the way belief creates ghosts when it dies. The adaption is also gender-flipped, narrated by a girl version of Henry Tilney, who, when you think about it, is a much more complicated character than the lovely milk-fed Catherine Morland. I’ve gotten too old for most YA, but this worked for me, and not just because of the intertext. Good.

Exit, Chased by Baron by Aydra Richards. This almost strays into sentimental novel territory, in that the main girl is a virtuous woman who suffers undeserved persecution with noble silence … but then eventually she drops the martyr act, thank God. The titular baron, the one both doing the persecuting and the romantic lead, also sees the error of his ways and settles into a satisfying amount of groveling. I love a good grovel. There’s also a somewhat questionable but nevertheless coherent intertext with Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, which is def one of the Bard’s very minor works. (I think it’s his last play, and most Shakespeare types believe he didn’t write the second half.) Not essential reading, but good for what it was.

Graphic. No, not that way. Ok, maybe a little that one time.

As I mentioned last year, I feel like I’ve lost whatever thing it was that kept me semi-current with comics, so it’s another poor showing this year. I should probably pick up some of the manga the kids are always entreating me to read.

Trees by Warren Ellis, et al. I read the three collected volumes of Trees — In Shadow, Two Forests, and Three Fates — because I started this series a million years ago and wandered off. Apparently, everyone else wandered off on this series too, because there are only three volumes, and it feels very unfinished. At some time in the recent past, alien megastructures have landed all over earth, shifting the climate both literally and politically. The trees work as a decent metaphor for climate change in the first two volumes, but the third hares off to a loosely connected plotline. Which would have been fine if this series continued, but as it stands, it’s disappointing and unresolved.

Square Eyes by Luke Jones & Anna Mills. While I love a dystopian cyberpunk hellscape — is there any other kind of cyberpunk landscape? — and I understand why this choice was made, the disjointed storytelling style was sometimes too opaque. The plot is a sort of PKD-style wigout, with characters moving through a kaleidoscope of memory and identity, which is already pretty disjointed. Still, the art was right up my alley and I bolted it down right quick.

Nils: The Tree of Life by Jérôme Hamon. A riff on Norse folktales in a high-tech/low-tech post-apocalyptic setting. The art is lovely. but the story itself felt a little shapeless. I don’t think the world-building was very good, because I was often perplexed by how things are supposed to work, and the cli-fi messaging felt loud? Or simplistic? But it was still a nice read. I’ve been chasing graphic novels which feel like Simon Stålenhag’s work, and this occasionally did.

Fine Print by Stjepan Šejić. The antics of lust demons and the heartbroken are the subject of this graphic novel. (Get it? Get it?? Phew.) I kinda wish I knew how this ended up in my holds, because I have no memory of putting it there. A lot more fucky than my usual tastes, Fine Print was nonetheless more wholesome and affirming than all the sex might imply. Šejić plays with the distinction between love and desire without prioritizing one or the other, a distinctly sex-positive take — so often sexual desire is treated as degraded. Better than expected, but there were still issues with samey looking people and a looser plot than I prefer (though that’s pretty typical with comics, so).

Punderworld by Linda Šejić. You’ll notice the same unpronounceable-by-me last name between this and Fine Print, so for sure I learned of one from the other. Cute retelling of Persephone and Hades, which doesn’t seem like it should be possible, given the various wretched aspects of the Greek myth: abduction, rape, incest. (And there are a lot of terrible dark fantasy takes on that myth, boy howdy.) Here, Hades is an adorable dork & Persephone effusive and sunny, and their descent into Hades is an almost slapstick tumble and not a gross violation.

Fantasy

Still reading a lot of lighter fantasy, which I assume will continue through the second Trump administration. I just don’t always have the bandwidth for harder stuff.

The Witch’s Diary by Rebecca Brae. Cute little epistolary number. It took me a minute to get into this, I think partially because the opening drags as our heroine fucks up job posting after job posting: she’s a post-college witch who has a big deal board accreditation in like a year, so she has to have a union-approved job for however long. But once things settle into a non-magical plane, aka modern America, I got a lot more invested and shot right through the last half. Sometimes a bit goofy for my tastes, it nevertheless had enough bureaucracy, casually well thought out magic, and genuinely funny slapstick to keep me happy.

Consort of Fire by Kit Rocha. Neat to see super queer romantasy with an emphasis on consent, but the first three quarters or more is so slow I struggled to stay engaged, and all the plot is back-loaded on the last couple chapters. This disengagement might be me, because this kind of high fantasy just isn’t my bag, and I don’t mean to ding the book for my predilections. I never did pick up the second in this duology, Queen of Dreams, but I might.

Books & Broadswords by Jessie Mihalik. Two cheerful but unremarkable fantasy novellas obviously written after the smash success of Travis Baldree’s Legends & Lattes. Both novellas included could be described as very loose retellings of Beauty & the Beast, but without a lot of danger. They both have dragons. I like dragons.

A Study in Drowning by Ava Reid. This YA novel is a cross between a Possession-style literary mystery and a haunted Gothic, which I’m 100% on board for. Especially because the Gothic was turned up pretty high: there were ghosts in diaphanous white dresses, a crumbling mansion, sins of the father, creepy townsfolk, etc. And the writing is very ornamented, just the right kind of overwritten for the subject matter. The pacing is slow and I didn’t feel the antagonistic heat between our leads, but this is one of those books which starts rough but ends well, which is way better than the reverse.

Bride by Ali Hazelwood. I feel like everyone read this book this year so you don’t need a plot synopsis, but here goes: A werewolf and a vampire have to marry to seal a treaty in a world where humans, weres, and vamps are at each other’s throats. It also manages to address a fantasy trope that I don’t see interrogated enough, namely the mate bond and what a huge nightmare being biologically obsessed with someone could potentially be. As I mentioned before, I’m into that. The dialogue is a lot of fun and I enjoyed the characters, even if it was occasionally aggressively trope-y. Oh, and I’m absolutely convinced Hazelwood thought to herself, “I am going to write a really tasteful knotting scene. Let’s mainstream that shit!” If you don’t know what I’m talking about, don’t google it.

A Matter of Execution by Nicholas & Olivia Atwater. The name of this novella is a pun because it opens with our hero being rescued from execution by his quirky shipmates, which should give you an indication of the general tone. After the rescue, it turns into a heist, yasss. Though this is solidly steampunky fantasy, it has peripatetic space opera vibes, which I may have mentioned I’m into. This novella is clearly a set-up for a series, and you can bet your ass I’ll be reading more.

One-Offs

Sometimes things don’t fit into neat categories. I would say most of these are on the literary end of things, so even if they have fantasy or science fictional elements — my tastes being what they are — I wouldn’t feel comfortable, exactly, calling them sff.

Escape from Incel Island by Margaret Killjoy. That title slays, right? Fun little ditty about an Escape-from-NY style prison island populated by incels lured there by the promise of free women. Five years later, two AFAB folk are sent in to retrieve something important left behind when the island was left to the neckbeards, resulting in a completely goofy pilgrimage through the various fiefdoms which coalesced in the intervening years. A lot of fun for an exploration of misogyny, which is generally not fun at all.

The Dreamers by Karen Walker Thompson. Like her debut novel, The Age of Miracles, The Dreamers will leave you with a pleasantly reflective sense of beautiful despair. The Dreamers details an epidemic of deep sleep caused by a virus and localized on a sleepy northern California college town. The novel had the unfortunate luck to be published in 2019, so there’s things in the plot that don’t quite ring true — the town is put under cordon sanitaire, for example, which would never happen in post-Covid America — but the tone is so musing and thoughtful, without a lot of over the top nonsense, which I really appreciate.

Depart! Depart! by Sim Kern. A Jewish trans kid ends up in the Dallas arena after Houston is functionally destroyed by a hurricane. A little bit cli-fi, a little bit apocalyptic, a little bit Jewish, and a whole lot queer. Normally I’m a bitch about this, but it’s third person present tense, which is fucking hard to pull off, so good job there. Kern uses ghosts — which are often avatars of our embarrassing, angry pasts — to very good effect, and I loved the main character.

Sleep Over: An Oral History of the Apocalypse. In a reverse of The Dreamers, Sleep Over is about an epidemic of sleeplessness, but the effect is universal, not localized. The story is told in the Studs Turkel-style format of books like World War Z. Like Brooks’ take on the zombie wars, the raconteurs sound pretty samey, but then the effects of profound sleeplessness seem well thought out. I read it on a flight after not getting enough sleep, which was also perfect. Also like WWZ, there were a couple sections I really didn’t like, but then the whole thing goes down pretty fast, so.

Corey Fah Does Social Mobility by Isabel Waidner. Something like both a satire and a po-mo farce, Corey Fah will have you saying “what the fuuuuuck” roughly one million times. The novel/la opens with the titular Corey winning a literary prize for the Fictionalization of Social Evils. In order to get the prize money, Corey must go round up a neon-beige blimp which remains stubbornly out of reach. That’s just the beginning of the weirdness. You know, I’m not going to pretend I got even half of what was going on in Corey Fah Does Social Mobility, but I know enough to say that ending was a banger.

The Reformatory by Tananarive Due. As it happens, I’m going to start and end this list with a book by Tananarive Due. The Reformatory, which just won a raft of well-deserved awards, is a lyrical, brutal, essential novel about reform schools in the Jim Crow south where many young Black men were incarcerated and then murdered. It’s the kind of horror novel, like Toni Morrison’s Beloved, where the stomach-turning horror is historical fact; the supernatural elements — ghosts, in both novels — might occasionally startle, but they’re not going to form a mob and burn your fucking house down with you in it. The best book I read last year.

Final Thoughts

There’s another dozen or so novels that didn’t make it on this list, for various reasons. I didn’t note a bunch of rereads — like Grace Draven’s Radiance or Colson Whitehead’s Zone One — which I tend to turn to when I’m not feeling great. I’m also working back through a couple Elizabeth Hunter series, most notably the Irin Chronicles, because I know she does something nuts with the concept of the mate-bond in one, but I can’t remember how she got there. I also read some stupid stuff that I don’t have much to say about, and I don’t feel the need to be a dick about on the internet. (Weird, I know.) There’s also a handful of books I started and couldn’t finish, sometimes because of me, and sometimes because of the book. Like I stopped reading Tananarive Due’s My Soul to Keep at about the halfway mark. In some ways, the story is like Anne Rice’s vampire books: a morally ambiguous immortal does a lot of fuckshit, has feelings. But I knew it was going to end badly, and I just wasn’t up for it. That one was 100% on me.

So! That’s my reading this year. God knows what I’ll get up to in 2025. Happy reading!