I have a fractious relationship with Quirk Books. No, fractious isn’t the right word, is it? Because they don’t know I exist nor do they (or should they) care about my opinion? I was excited for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies because the idea rules, but then it turned out soggy and under-heated. But then came the clones – Jane Slayre: The Literary Classic with a Blood-Sucking Twist, The Meowmorphosis – which mimeographed this idea into a purple-blue stew of end-cap bait, finally culminating, for me anyway, in the dire shit-show that was Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls. That book made my blood boil.

I have a fractious relationship with Quirk Books. No, fractious isn’t the right word, is it? Because they don’t know I exist nor do they (or should they) care about my opinion? I was excited for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies because the idea rules, but then it turned out soggy and under-heated. But then came the clones – Jane Slayre: The Literary Classic with a Blood-Sucking Twist, The Meowmorphosis – which mimeographed this idea into a purple-blue stew of end-cap bait, finally culminating, for me anyway, in the dire shit-show that was Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls. That book made my blood boil.

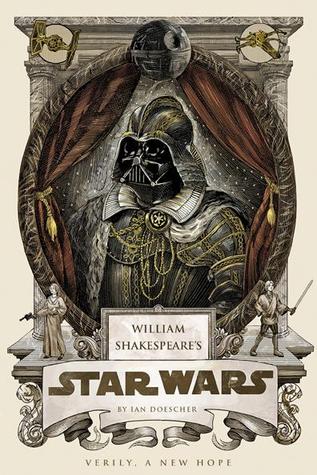

Because, look, I don’t really mind end-cap bait, and I don’t mind the toilet reads that publishers put out to give my non-reading friends and family something to give me when my birthday rolls around. (“I know you like Jane Austen! I think you’ll love this!”) I’m not even being an asshole when I say I appreciate the thought. So when the illustrious and inimitable karen sent me William Shakespeare’s Star Wars out of the blue, I thought, uh oh, I’m going to have to make the choice between my desire to shittalk this book, and being a grateful and worthy human. Again! Why am I such a terrible person? etc.

But as it turns out, hey Mickey! She likes it! So, phew. There’s a dry conversation one can have about translations: which is better, a translator writing from the original language, or one writing to the target language. Is the translator’s mother tongue the original or the translated language? My own take is that it’s almost always better to write to the target language. I once read this biography of Rasputin that was obviously translated by a native Russian speaker, and while it was often hilarious, and I enjoyed the wobbly prose as a desultory Russian language student, you just can’t mix verb tenses like that in English, товарищ.

I think there’s something of the translation problem in the mash-up, for the reader at least. P&P&Z was probably more aimed at the Austen nerds, because the zombie parts were really more about ninjas, and big swaths of the text were from Austen herself. So you rate it as an Austen nerd, not a zombie nerd – if you happen to be both, like me. (A straight up zombie nerd should probably just stay away.) As an Austen nerd, it was mostly just perplexing, like, what exactly are you saying about Charlotte? Also, you get that messing with the chronology messes with…oh Jesus, nevermind. I really liked the cover and study guide, so I guess thanks for that, Quirk Books.

By the time Dawn of the Dreadfuls rolled around, that book managed to drop trou and dump on both Austen nerds and zombie nerds – remember, I’m both, so double dump for me – which turned the translation problem into a Zen koan of Not Giving a Fuck. If the translator in question doesn’t care about either language, that’s what you get. (And I’m going to throw in the disclaimer that if you’re neither kind of nerd – Austen nor zombie – then you’ll probably think whatever about all my shouting.) Point being, it is clear to me that Doescher is a Star Wars nerd – that’s the language he is translating to – which I think is a pretty good choice. I’m going to wince when he drops a Naboo reference because I spend a fair amount of energy pretending the prequels never happened, but then I’m also going to hand-clap about a sly reference to nerf herding, which, you know, wasn’t a thing until The Empire Strikes Back. Ahem. Shut up.

So this isn’t really for Shakespeare nerds. (Do you people exist? I mean, I’m sure you exist, but are you reading slovenly populist Internet reviews?) I wrote this whole thing aping Shakespeare to start my review, but it turns out when I try to write that way, I end up sounding like a pirate. Avast, me hearties! God’s teeth! and all that. So, we’ll give Ian Doescher some props for pretty solid metered dialogue, plus he manages to pull off an occasional heroic couplet that made me smile. I did spend some time discovering this handy nit-picker I got as a booby prize for being an English major had somehow gotten into my hand, and then having to put it away. I’m like an unconscious nit-picker fast-draw, matey. All the short’ning o’ words wit’ apostr’phes to make fit the met’r makes me freak out. Just, ugh. Also, I kept thinking things like, “Other than maybe the chorus in Henry V, who is present at the beginning of every act, Shakespeare didn’t really use a chorus throughout the action like that. That’s really more a feature of Classic Greek playwrights.” But then I gave myself a wedgie. Language from, babies, even if it’s kinda dumb. It’s dumb with jokes about R2D2 monologuing about stuff as an aside, which is pretty freaking fantastic.

So thanks, karen. This rules.