I picked up Wake last week when I was up north. Amanda Hocking is a Minnesota writer, whom you might have heard of because she is a self-publishing superstar. I think her success story is just adorable, I kind of love everything about it, and I’d resolved to read something of hers eventually. I was under the mistaken impression that Wake was about mermaids living in Lake Superior, so this seemed like the logical place to start. You know, because I would read the crap out of a novel about mermaids in Lake Superior. Wake is about mermaids (sort of, more sirens than half-fish ladies) but the locale is the Maryland coast. Not that my disappointment about locations really has anything to do with anything.

The novel opens with a chatty, boppy little opening, establishing our two point of view characters, Harper and Gemma Fisher. The names are pretty indicative of tone. Gemma is our 16 year old protagonist, and clearly she was named first. Her name’s kinda chick-litty and unlikely – Americans don’t name their kids Gemma, and it reads as exotic/fancy – with a cute little metaphorical implication of someone named fisher being in a siren book, right? But then Harper Fisher? This is just straight up a terrible name, and I find it hard to imagine the kind of people who would saddle their kid with two occupations as monikers. Or if I can imagine them, they look very different from the parents here.

These are book names: romantic, lightly metaphorical, and also kinda girly milquetoast. Gemma Fisher is what you want to be named when you’re 14 and someone just mangled your oddball Celtic name for the umpteenth time and then asked you if you had a nickname. No, fool, I would have just given you the nickname instead of going through fifteen minutes of you acting like I made my name up to make your life hard. Well, that escalated quickly. Also, I never wanted to change my name, but I can totally see the appeal of names like Gemma & Harper to teens, who were named Jennifer and Kristen before there were 27 Jennifers in every class, and they want in on the new name that there will be 27 of in every class.

The opening of the novel sets up the sisters’ lightly sniping relationship, and a couple of boy love interests for the sisters, in addition to foreshadowing you with a two-by-four about a pack of mean girls. Harper and Gemma’s mom is packed away in a home because of a traumatic brain injury; their dad ain’t handling it so well; Harper more or less acts as Gemma’s mom in a caring but overbearing way, blah blah blah. This is going to be an uncharitable thing to say, but I thought of the writing advice attributed to Elmore Leonard: don’t write the parts people skip. So much of this was skippable, from reams of unnecessary dialogue – seriously, I did not need a whole run down of the breakfast options this morn – to the logistical wranglings – hey, I left my bike at the pool; can I get a ride – to the artless but inoffensive prose. It was nice that Gemma’s paramour was the sweet, nerdy boy-next-door, but, gotta say, their relationship had zero juice.

I ended up just giving up because I could just see this muddling on to its three-star conclusion. I’m going to dig parts of it because I can see that it focuses pretty strongly on female relationships, and that is something depressingly lacking in a lot of YA. (Hell, in a lot of fiction, period.) The tension is going to be about Harper and Gemma’s relationship when Gemma gets all siren’d up; plus, sirens are a pretty weighty metaphor about female sexuality, etc. But there’s going to be a half dozen things that make me bananas, like Gemma’s solo night swims in the ocean. Everyone’s on her for it because she’s a swim team star and shouldn’t waste her swimming at night or something? No. Do not swim alone at night in the ocean ever. Don’t swim alone. I don’t care how strong of a swimmer you are; they might never find your body.

Like the names, the night swimming is included because it sets up this romantic situation – ah, the water in the moonlight – but it doesn’t make sense that a swimmer wouldn’t have very basic water safety drilled into her by her coach, who would do more than sigh and shake his head if he found out about it. Oh, also, mama’s crazy, and I can see that going nowhere good. But! I can see why Hocking is so successful. It’s real mundane, but in a way that makes the mundanity just a little bit shiny. Gemma’s a good girl and Harper’s a book nerd, (I’m a good girl and a book nerd!) and they have pretty boring problems, (I have pretty boring problems!) you know, until dun dun (omg, college!).

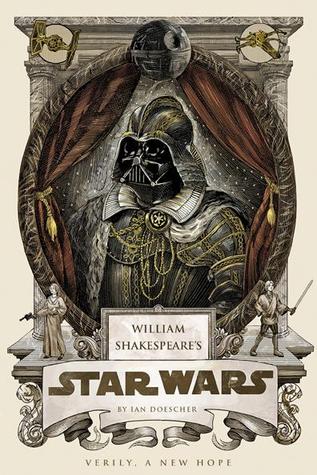

I can also see the appeal of the girlishness of the whole package here. I showed my six year old daughter the cover – and my daughter is a damn fine barometer of girlishness – and she was pretty into it. But then I peeled the cover off and showed her the poster that’s secretly on the back of the book jacket.

She more or less freaked out about it. What are they doing? I want to go swimming too. Wake isn’t going to be about saving the world or huge action sequences. It’s not going to culminate in fisticuffs or explosions. Instead, it’s going to be this chatty, actionless parable about not fitting in and growing up and female sexuality, which is going to resonate for girls on exactly the same tuning-fork frequency as Twilight. I honestly think that’s great, the whole girl pulp for girls thing, and Wake seems to be ahead of the curve in terms of not being regressive and reactionary about female relationships slash sexuality.

But I am, alas, old and cranky, and this just is way not for me. Frankly, Gemma and Harper are so muted, such nice people, that I had a hard time relating to them. (And that thing where girls can’t tell if they’re horny or just embarrassed – she wondered at the blush creeping up her cheeks, etc – is just weird. Can’t you tell that at a pretty young age?) I figure if I want to hear a story about a coven of mean girls, I’ll just re-watch The Craft.