1940 edition of Leaves of Grass which contains illustrations from Lewis C. Daniel and an introduction by Christopher Morley. I believe the illustrations are from 1928.

She received this as a gift, and when I go to ask her, her mouth can’t form the words. I think I hear the name Kathy, and maybe a Mc, but the throat goes to glottal stops after a stroke. I don’t want to talk about this.

Dad and I are standing in front of the farm house, and it’s throwing light into the cicada buzz of Indian summer. We stand near forward, turned in a little the way Minnesotans do, elbow to elbow. He’s got a look in his eyes I can’t consider too closely without losing it. I smoke, and it rolls in the porch light. Dad talks. I talk. We tell stories about people we know. I am so angry and sad. There’s a house full of people, and we can hear their chatter and light-making. She is in the back room, my sister at her side. I don’t want to talk about this either.

It would have been not so long before she was married when she got this book, but the flyleaf notes her maiden name – Doris Bahls, R.N. It’s covered in green wool burlap and has a slipcase. It is sun-faded. We thought at first this was a gift upon the completion of nursing school, but that would have been two years earlier than the publication date. Dad read her “Song of the Open Road” that morning. We talk about Whitman. Dad is incandescent, surprised. He is a farmhouse throwing light into an angry darkness.

I knew these assholes in college who ruined Whitman for me, the way assholes who own literature do. You know the kind: the Brahmans wielding citation. My anger at her dying spills into my memory, which is already angry enough. Sometimes, like now, my instinct to anger depresses me. I resolve to read more aloud to her, if she wants to hear, tomorrow morning. That afternoon I saw a piliated woodpecker batter the lightning-struck tree on the roadside. It seemed prehistoric and a pathetic fallacy. I wanted to feel wonder, but my anger kept getting in the way.

The morning is better. I think murder to my aunt when she pulls bullshit both too complicated and subterranean to explain to anyone but my sister, but that infraction bleeds out into an empty house and my sister and I quiet and sitting. She reads aloud, and I listen. I don’t take in much meaning. Grandma isn’t awake, but she isn’t asleep either. Rain threatens – the sky hanging low and still – and the morning is napping and expectant. We hear the burr of the lawnmower pushed by the aunt who makes me angry over an acre of land. The sound is an odd comfort. Work is good.

My sister finishes, and there’s silence and low murmurs. Coffee cups are refilled. We turn her body the way the post-it on the wall instructs to do every four hours, asking if this pillow is right. God, she’s so thin. She smiles so big that she is radiant. On her bed is the quilt made by her grandmother when she was nine, in the year before her grandmother had the stoke, and then never spoke again. I don’t want to talk about this. I read “O Pioneers!”

I start to read “Song of Myself”. I begin choking in places, the early parts about the immortality of grass, the green hair of the grave. I keep thinking of Dylan Thomas, and the synagogue of the ear of corn or the fern on the windowsill dropping its seeds. I think about finding Fern Hill and the eulogy to Ann, but these poems are bright with loss for other people for me, and I’m not exactly keeping it together already. Whitman reminds me of the Beatitudes: blessed are the angry and sad. Blessed are the dying.

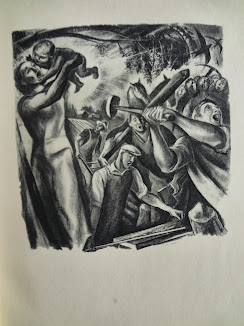

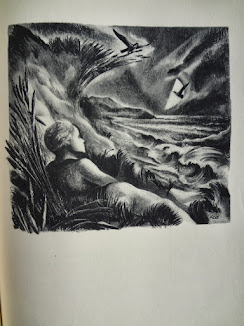

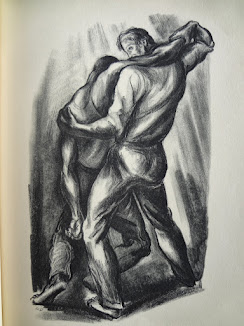

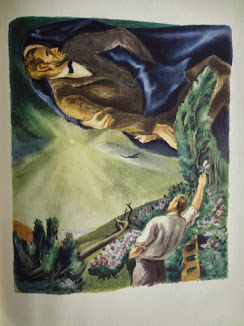

I read for a long time. My sister is laid out on the day bed in front of open windows. She watches the ceiling or closes her eyes. She listens. My voice begins to go muzzy, and I page through, counting. I didn’t know this poem was so long. It is repetitious until it nails you, a lulling patter of window-struck rain until lighting strikes the tree out front. I don’t even know what to do with the illustrations, which embed hammers and sickles in nearly every plate, Abraham Lincoln flying like one of Marc Chagall’s lovers over the rooftops, wrapped in the arms of a dark figure. I don’t think but store them away.

It eventually rains. The house fills with people who fill my anger, and I retreat to the porch, sitting off the edge, talking on the phone, tamping cigarettes into the gravel. I sit at the edge of her bed and read her anecdotes from James Herriot about dogs while dinner occurs like a rainstorm. I don’t want to talk about this either, and I don’t have an ending.

Oh, Ceridwen, what I’d give to be able to write like you.

I <3 you, Brian.

Beauuuuuuuuuuuuty!