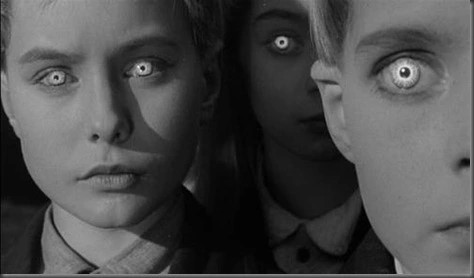

I didn’t know what to expect going into the newest BBC adaption of John Wyndham’s 1957 novel, The Midwich Cuckoos. The previous two adaptions — one in the 60s and the other by John Carpenter, of all people, in the mid-90s — were uneven and didn’t quite catch the vibe of the novel. The 1960 version, retitled The Village of the Damned, came the closest, I thought, managing to capture the eerie sameness of the Children and their intense relationship with Zellaby, but it, probably inevitably given the runtime, flattens the motivations and horror of Zellaby’s final act. With a television series there is an opportunity to really dig into the implications of an alien invasion narrative that positions our very own children as a racially constructed other, and then blows them the hell up in Darwinian “self-defense”. The themes of The Midwich Cuckoos could quite easily map to contemporary concerns like reproductive rights, the mis/treatment of migrants and refugees, homegrown right-wing terrorism, or even the ongoing genocide playing out in Palestine.

Alas, that’s not what happens, at least not in the first two episodes, “Bad Things” and “In This Together.” These first two episodes cover the Dayout, in which the entire town of Midwich was rendered unconscious, up to the birth of the children conceived that night by every pregnancy-capable person in the village. (I should say that the Dayout is how the people in the novel refer to the event; the adaption sensibly changes this to March 6, which is how people would refer to it. 9/11, J6, October 7: we often refer to calamities by when they happened.) In the novel, this opening section has all the elements of a farce at times, relayed in a wry, lightly satirical tone. The narrator himself is an outsider, and his description of the town and its denizens mockingly affectionate. The town itself is described as consummately English in a sleepy, uninteresting sort of way, and the townsfolk have the kind of insular mistrust of outsiders borne out of living in each other’s pockets their whole lives. Wyndham excels in creating a sense of place, painting a portrait of its people, so that when the shit starts hitting the fan, the reader has a solid heatmap of the societal architecture the town.

The fist episode, by contrast, does not do an exceptional job of creating a sense of place, of community. We get some scenes where various folk telegraph their backstories in obvious ways: a couple moves into Midwich from maybe London, there’s some tension with her family because she’s white and he’s Black; a therapist has a sullen college-age daughter who snarks on her when she goes to a date in Birmingham; a taciturn cop has a beatifically pregnant wife and a sassy sister-in-law; and so on. None of these people have anything to do with each other, which I think just blows the whole way Midwich works as a microcosm of England itself. The book is called The Midwich Cuckoos, because the place itself is important, and then Wyndham lays on its Englishness with a trowel to make sure you really get it. And absolutely, that sort of town doesn’t really exist anymore so the scenario requires updating — the series cast is racially diverse, which is correct — I just thought that update could be more interesting. These characters have the most drearily obvious motivations and character traits — taciturn cop is taciturn! his pregnant wife is surely marked for death! the therapist’s daughter will be a problem later! — which makes everything that happens inevitable and therefore dull.

My biggest problem with the way “Bad Things” depicts the Dayout, though, is the tone. The opening of the novel is wryly funny in an understated way. The way the military tests the boundaries of the affected area by walking in soldiers who then pass out and have to be dragged back out gets increasingly farcical, as is their attempt to lower a cage of ferrets into the town, you know, for science. His description of how the townspeople come to understand that everyone is pregnant is similarly wry, but in the way that humor often covers for things that can’t be talked about. This is how the narrator describes what must be a number of self-induced abortion attempts:

One not-so-young woman suddenly bought a bicycle, and pedaled it madly for astonishing distances, with fierce determination.

Two young women collapsed in over-hot baths.

Three inexplicably tripped, and fell downstairs.

A number suffered from unusual gastric upsets.

It’s oblique but winking, discussing unmentionable topics by coming at them sideways. The way Wyndham alludes to these abortion attempts suggests whole unspoken lives, almost a metonymy of the secret lives of women. The town meeting where the women discuss the pregnancies is extraordinarily sensitive to the concerns of women — much more than I would expect from a writer of Wyndham’s gender and generation.

In the series, by contrast, the fact that all the women have fallen pregnant is shown through them all cradling their bellies in the universal sign for “I’m preggo” while smiling big happy smiles, which I absolutely hate. There isn’t the dawning horror and rumors, nor much acknowledgement of the hardships ahead for the underage and unwed. The town meeting is an excuse to manufacture some solidarity I don’t buy. A couple women decide to continue the pregnancy for their own reasons, and those reasons are given voice: a woman who was told she was infertile; a religious woman; whatever the therapist’s daughter was on about. A much larger group opts to terminate their pregnancies, but something, presumably their unborn children, forces them to leave the clinic. No one gives voice to how fucking horrifying it is to be forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy. Given the current political climate, there is an opportunity here to talk about enforced procreation and how seriously that sucks, but we skip right over that to scenes of heavily pregnant women who seem to be pretty chill about gestating a brood parasite. It’s not great, Bob.

I did like the second episode, “In This Together,” better than the first. I thought there was some attempt at more interesting camera work — the first episode seems to be filmed in small-town-procedural-o-vision — and the director does a decent job of lingering on the pregnant body in ways that make it seem uncanny or unnatural. There are a couple scenes which show gravid bellies roiling with the unborn child, which made me flash on my own pregnancies, the times I could see a foot or an elbow protruding through my skin. And I wasn’t even gestating an alien; that’s just what happens. Pregnancy is a terrifying time, ripe for horror, and the second episode does touch on some of that.

All in all, the first two episodes of The Midwich Cuckoos ended up being a rote and uninspired, a series of squandered opportunities. Given that episode two is better than one, I have some small glimmer of hope this series won’t be a total wash, but I’m not holding my breath.