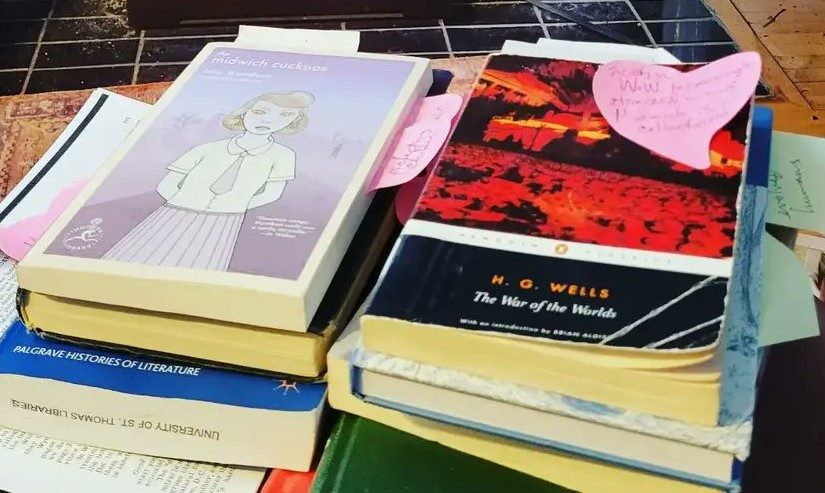

The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham deliberately invokes The War of the Worlds to repudiate the concept of social Darwinism, but in such a way to be legible to a post-war audience. The Midwich Cuckoos, a novel about a group of otherworldly children born to a quiet English village, doesn’t look much like an alien invasion story, let alone Wells’s Martian invasion. A flying saucer is photographed on the town green during an event called the Dayout, in which the entire town is rendered unconscious, and all the women of childbearing age become pregnant. This photo and some impressions in the grass are the extent of the direct evidence that the Children – as they come to be known – are alien in nature.[1] Indeed, the sometime authorial mouthpiece, Dr. Zellaby, posits that the Children aren’t alien so much as the next iteration of human (Wyndham, 197). Like the strangeness of describing the birth of sixty-odd children as an alien invasion, it seems odd that the events in The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells are described as a war at all. Technologically superior Martians do, indeed, invade Surrey, but the Edwardian British military is so outmatched there is only the most cursory resistance. The invasion continues unchecked, until the Martians are felled, ironically, by the “transient creatures”[2] of bacteria. The war alluded to in the title is one of evolutionary struggle: because humans have been locked in “an incessant struggle for survival” with microorganisms, we have developed a resistance to their ill effects (Wells, 168). The Midwich Cuckoos is in dialogue with The War of the Worlds throughout, updating and localizing the Wellsian position against social Darwinism in what is best understood as a post-Holocaust novel.[3]

Several times in the novel, Wells invokes the contemporary debate between T. H. Huxley and Herbert Spenser. Huxley was vigorously opposed to Spenser’s concept of “evolutionary ethics:” that societies are subject to the same evolutionary forces as individual biota, and that this evolution always tends toward higher forms. Spencer saw the competition apparent in nature as an appropriate model for human ethical conduct. To wit: society should be constructed to allow maximum competition between individuals, with the accumulation of wealth as the indicator of “fitness.”[4] To Huxley, fitness in biological terms didn’t equate to moral rightness, and evolution was a biological process that didn’t require our intervention. Put another way: society is not natural process like evolution, a process which is morally neutral precisely because it is outside of our control.[5] That being said, the Darwinism in The War of the Worlds does perform a moral function, and the themes of the novel are overtly about the conflict between science and religion, and the brutality of colonialism. Wells uses the Martian invasion to illustrate to his Imperial British audience what it might feel like to be colonized by a technologically superior force.[6] Sarcastically invoking the language of social Darwinism, the unnamed narrator lays bare the cruelty of colonialism:

And before we judge of [the Martians] too harshly we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought. […] The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit? (Wells, 9)

The extermination of the Tasmanians is attributed to “our own species,” not the British Empire. The Tasmanians themselves have a “human likeness,” but ultimately aren’t human. Blaming rote biology and Darwinian competition for the destruction caused by colonialism both justifies and excuses that violence. It is all to the good of the species, in the end.

Another reason The War of the Worlds reads so strangely to a modern audience is because it was written before both world wars. This leads to odd little moments, like when one of the rubberneckers at the site where the Martians’ cylindrical craft has landed suggests building a trench around the craft, and his friend responds, “You always want trenches” (Wells, 39). Given the British experience in World War I, the mention of trenches becomes ruefully comic, an accident of history Wells certainly couldn’t have anticipated. Though Wyndham’s experience of the World Wars was almost exactly as he describes Gordon Zellaby’s – “Too young for one war, tethered to a desk in the Ministry of Information in the next” (Wyndham, 15) – the cultural, and, in some cases, literal landscape had profoundly changed in the time between the two novels’ publication. The man christened John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris wrote under a half a dozen pen names during his life, all of them variations and permutations of his given name.[7] His works in the 1930s, when writing for largely American pulp science fiction magazines, are in line with their contemporaries: often occurring on spaceships peopled with Venusians or Martians, occasionally with lurid, sexualized covers.[8] But the outset of World War II put an end to the era of pulp serials of the 1930s, and the Beynon and Harris personae. While a couple short stories written before the War were published during, he wrote no fiction during the war years. During the Blitz, he lived and worked in London as a censor for Military Intelligence,[9] and eventually joined the war effort directly, including taking part in the Normandy Invasion. It isn’t until 1951 that he publishes a novel under the Wyndham name. While the John Wyndham novels in some ways have the ornament of earlier pulp serials – ambulatory carnivorous plants![10] abyssal aliens![11] – they work by “submerging his fantastic element”[12] into the everyday in the tradition of H. G. Wells. In The Midwich Cuckoos, John Wyndham reaches back before both World Wars, and updates The War of the Worlds, the original British Invasion narrative.

Wyndham manipulates the reader into identifying with the concentration camp guard, whose moral imperative is to commit genocide, paradoxically to save civilization.[13] As Zellaby, the man who detonates the bomb, says days before the end: “It is our duty to our race and our culture to liquidate the Children” (Wyndham, 201). Not kill, not defeat – liquidate the Children. Just after this stunning utterance by a man who has acted as father figure and teacher to the Children – in addition to functioning as the expository mouthpiece – Zellaby yet again invokes Wells, bemoaning how Wells didn’t anticipate a moment in history when governments contemplated – then perpetrated – the systematic eradication of their citizens.

Take H. G. Wells’s Martians, for instance. As the original exponents of the death-ray they were formidable, but their behavior was quite conventional: they simply conducted a straightforward campaign with a weapon which outclassed anything that could be brought against it. […] Yet, over-all, what do we have? Just another war. The motivations are simplified, the armaments complicated, but the pattern is the same and, as a result, not one of the prognostications, speculations, or extrapolations turns out to be of the least use to us when the thing actually happens (Wyndham, 180-81).

The invasion of Midwich by its own children and their eventual destruction is not “just another war:” it is something decidedly worse. Zellaby uses the language of Darwinism to conceptualize and situate the Children of Midwich, invoking the social Darwinism used to justify some of the most horrific atrocities of the 20th Century. Social Darwinism recasts a fight for “our way of life” into an existential struggle, and ultimately, a zero-sum game.

Welcome to Midwich

From the very beginning there are several similarities between The War of the Worlds and The Midwich Cuckoos, the most foundational being the sense of place. The events in the Wells novel are so perfectly mapped to turn of the 19th century Surrey and London that a contemporary reader would feel deep familiarity with the landscape.[14] For a reader at a remove of place and time, this can be alienating in and of itself, so the most successful of adaptions – such as Orson Welles’s 1938 radio play – retain the original novel’s almost documentary feel. In his radio play, Orson Welles relocates the invasion to Grover’s Mill, New Jersey,[15]and the action moves through similarly legible locales towards New York City. This verisimilitude famously resulted in more than a few listeners taking the story of invasion as fact.[16] Situating alien horror in carefully recreated local spaces both imbues the alien with a sense of reality and heightens the effects of the horror.[17] Wyndham also details the locale of Midwich, site of his alien invasion, with cartographic clarity; the first chapter is given almost completely over to description of the town and the second its inhabitants. Like The War of the Worlds, the portrait of the mundane detail of Midwich foregrounds the uncanniness of the Children once they arrive on the scene. The key difference in these portraits is two-fold: first, the town of Midwich doesn’t exist, and second, the portrait is satirical.

Midwich is positioned as a sort of everywhere and nowhere, embodying an “Arcadian undistinction” of composite and consummate Englishness. “The vicarage is Georgian; The Grange Victorian; Kyle Manor has Tudor roots with numerous later graftings. The cottages show most of the styles which have existed between the two Elizabeths” (Wyndham, 6). The town’s minor claims to fame are so minor they would only ever be known to locals, and the narrator’s description pokes some gentle fun at various English luminaries. “Other events include the stabling of Cromwell’s horses in the church, and a visit by William Wordsworth, who was inspired by the Abbey ruins to the production of one of his more routine commendatory sonnets.” When the narrator, Richard Gayford, returns to Midwich to find the road into the town blocked, it is made all the stranger due to the “simple ordinariness of the place” (Wyndham, 5). Consequently, the events of the Dayout – the 24-hour period in which the inhabitants of Midwich lose consciousness and 61 women become pregnant – has all the elements of a farce. People, cows, cars, buses, ambulances, and any other creature that strays into the influence of the invisible dome over the town fall unconscious in visible but unapproachable heaps. On the other side of the line, a corresponding collection of rubberneckers, firemen, constables, and a not insignificant number of military men collect, trying to ascertain the scope and radius of the affected area. This culminates in two ferrets being dangled over Midwich in a helicopter, at about which time the people of Midwich revivify, presumably to the ferrets’ relief (Wyndham, 22-34).

Unlike the locations in The War of the Worlds, Midwich can feel generally familiar to anyone because it is not precisely familiar, but the satirical nature of the portraiture cues us into the fact that not everything that occurs in the novel is to be taken at face value. Midwich is encased in a dome and scrutinized by an increasing military presence in the beginning, and ultimately, that dome never comes off, and the military presence never relents. Starting with the Dayout and continuing through to the Children’s psychic compulsion which entraps the locals in roughly the same space, the town of Midwich is effectively isolated from their neighbors, and from larger British life. Even before the pregnancies are discovered or the Children born, military intelligence endeavors to hush up the Dayout. The diegetic reason for suppressing information about the Dayout, at first, is the presence of The Grange, a scientific research installation run by the military within the affected area. This furtiveness seems to be a reflexive act by a society still on a military footing after the end of World War II, because even the Colonel in charge of “Operation Midwich” doesn’t know what the Grange does. “Trouble is, for all we know it may be some little trick of our own gone wrong. So much damned secrecy nowadays that nobody knows anything” (Wyndham, 28).

Given the publication date and the internal timeline, the Children must have been born in the two years after VE Day. Many of the major characters are former (or current) soldiers – including the narrator, Richard Gayford, his war buddy now in military intelligence, Bernard Westcott, and Gordon Zellaby. The events of the Dayout are put under “the intimidating muzzle of the Offical Secrets Act” (Wyndham, 40). All through the novel, the relationship between the Children and the larger world is discussed in military terms: the impending birth of the Children is referred to as “D-Day” and a “battle” for which they’ve booked a “commando of midwives” (Wyndham, 78-79), and after their birth the vicar, Mr. Leebody, observes: “It has been a battle, […] but battles, after all, are just the highlights of a campaign. There are more to come” (Wyndham, 86). A militarized society has turned its gaze inward, towards the next generation.[18]

The Narrator

The narrative style in The Midwich Cuckoos leans hard on what Damon Knight calls “Wellsian retrospective clarity”[19] – subjective narration with the imprimatur of an objective perspective. Like in The War of the Worlds, the events in Midwich are related at a comfortable remove in time, a “narrative focalization which invests the text with the aura of authenticity.”[20] The reader never questions the information provided by the narrator in The War of the Worlds, despite the narrator being untrustworthy in several key regards.[21] In the rhetorically masterful opening, the narrator details the motivations and preparations of the Martians. The Martians “scrutinized and studied humanity,” and “slowly and surely drew their plans against us” (Wells, 7). At no point does the narrator mention humans and Martians meaningfully communicating, even in the six years following the invasion; he simply cannot know this about the Martians’ intent. His assertion is instead designed to shock Wells’s contemporaries out of their “infinite complacency” (Wells, 7). Because these assertions are made at the very beginning, the narrator’s suppositions are presented as fact in a way the audience won’t question, even if they are never corroborated.

In The Midwich Cuckoos, the narrator, Richard Gayford, and his wife Janet are new members of the Midwich community. Despite their year spent living in Midwich, transplants are rarely considered a local after the passage of several years (and, indeed, often not even after the passage of several decades.) He’s further at a remove in that he and his wife were absent for the Dayout, and therefore avoided gestating one of the Children themselves. The opening of the novel, wherein he details the events of the Dayout and its direct aftermath, are within his lived experience – a first-hand account. But it doesn’t take long for the narrative to spread beyond what our narrator himself experiences. Richard himself addresses this:

And now I come to a technical difficulty, for this, as I have explained, is not my story; it is Midwich’s story. If I were to set down my information in the order it came to me I should be flitting back and forth in the account, producing an almost incomprehensible hotchpotch of incidents out of order, and effects preceding causes. Therefore it is necessary that I rearrange my information, disregarding entirely the dates and times when I acquired it, and put it into chronological order. If this method of approach should result in the suggestion of uncanny perception, or disquieting multiscience, in the writer, the reader must bear with it the assurance that it is entirely the product of hindsight (Wyndham, 46).

At this point, the narrative assumes almost a third person impartiality for the second act, only occasionally broken by Richard’s often milquetoast interjections or his wife Janet’s more pointed barbs. Like the Wellsian narrator, Richard is part of the action, but often peripherally. For instance, several chapters of The War of the Worlds are given over to an account of the Martian invasion told from the perspective of the narrator’s brother.

Wyndham makes several important changes to the Wellsian storytelling style which subtly undercut the overt message and its messengers. Many of the biographical details from Wells’s narrator are relocated into the character of Dr. Gordon Zellaby. Zellaby and the narrator from The War of the Worlds are writers of cultural criticism, of the type that largely exists to be ironic considering subsequent events in the novel. (Richard is also a writer, but there is one allusion to his publisher on the first page, and it is never mentioned again.) Zellaby’s son-in-law says about While We Last, one of two of Zellaby’s Works named in the text: “It had been an interesting, but, he thought, gloomy book; the author had not seemed to him to give proper weight to the fact that the new generation was more dynamic, and rather more-clearsighted than those that preceded it…” (Wyndham, 12). The other named text is, fittingly, The British Twilight (Wyndham, 75). The unnamed narrator in The War of the Worlds, at the time of invasion, is “busy upon a series of papers discussing the probable developments of moral ideals as civilization progressed” (Wells, 12). When he returns home after the novel’s cataclysmic events, he finds his work in progress interrupted at the moment of (no doubt now thoroughly wrong) prognostication: “’In about two hundred years,’ I had written, ‘we may expect–‘” (Wells, 176).

Wyndham relocates the expository authority to Dr. Zellaby, while the voice of credibility – scientific or otherwise – resides in the unnamed narrator in The War of the Worlds. Largely Richard serves to ask prompting questions when Zellaby is holding forth; Wells’s narrator can more than hold forth on his own. In The War of the Worlds, because the narrator can control how his expository scientific speculations are perceived, we tend not to question some very questionable things. The narrator only tells us in the epilogue that his “knowledge of comparative physiology is confined to a book or two” and that the operating theory in the narrative for the Martians’ sudden, collective demise – that they have no natural resistance to earthly bacteria – is an assumption “so probable as to be regarded almost as a proven conclusion” (Wells, 175). Because he’s the one telling the story, he can present his subjective experience as objective fact. He boasts: “Now no surviving human being saw so much of the Martians in action as I did” (Wells, 128), but we have no way of knowing if that is true.[22]

By splitting the functions of the narrator in two, Wyndham ends up undercutting both Richard and Zellaby. This split creates the opportunity for the depiction of contrary reactions to Zellaby’s Darwinian speculation. In one humorous instance, Richard glances over at his wife, Janet, which shows him she’s not listening anymore. “When she has decided that someone is talking nonsense she makes a quick decision to waste no more effort upon it, and pulls down an impervious mental curtain” (Wyndham, 117). Richard, who is narrator but not mouthpiece, can subtly impact how that mouthpiece is perceived by showing reactions other than his own. While there is occasionally pushback against the narrator in The War of the Worlds, he can frame those objections as meritless or specious. The narrator at one point falls in with a curate, and the curate’s reaction is like Janet Gayford’s reaction to Zellaby. “I began to explain my view of our position. He listened at first, but as I went on the dawning interest in his eyes gave place to their former stare, and his regard wandered from me” (Wells, 71). At this point, the curate interrupts, ranting in biblical terms. The narrator responds by questioning the curate’s manhood and derisively dismissing his theology. “Do you think God had exempted Weybridge? He is not an insurance agent, man” (Wells, 72). The curate’s inattention to the narrator’s exposition says something about the curate – that he is hysterical and irrational – while Janet Gayford’s inattention to says something about Zellaby’s theorizing – that it’s nonsense.

While Zellaby’s disquisitions don’t have the imprint of a true narrator’s authority, Richard is a much more damaged narrator than the one in The War of the Worlds. Once past his own (slight) involvement with the Dayout, everything that Richard Gayford records must be an aggregate of information told to him by the people of Midwich, and subject to the same embellishments and distortions of any collected folklore. This becomes most apparent when Richard recounts events for which not only was he not present but were not attended by any other men. After the powers that be – the vicar, the doctor, and Zellaby, critically – figure out that all the pregnancy-capable people of Midwich are capably pregnant, they set up a town meeting to be managed by the brusquely efficient Angela Zellaby, Dr. Zellaby’s wife. This is after the men decide not to inform the women of the likely alien nature of their pregnancies, something Zellaby blithely refers to as “benign censorship” (Wyndham, 58). During the meeting, it becomes clear that the women already know this. Angela’s opening statement alludes to this directly: “If any married woman here is tempted to consider herself more virtuous than her unmarried neighbor, she might do well to consider how, if she were challenged, she could prove that the child she now carries is her husband’s child” (Wyndham, 64).

The meeting itself is precipitated by the attempted suicide of a pregnant 17-year-old, information which is relayed to the reader after a long list of abortion attempts.

One not-so-young woman suddenly bought a bicycle, and pedaled it madly for astonishing distances, with fierce determination.

Two young women collapsed in over-hot baths.

Three inexplicably tripped, and fell downstairs.

A number suffered from unusual gastric upsets (Wyndham, 52).

The words “pregnancy” and “abortion” do not occur in the text. Instead, information is conveyed stating plain facts, with a twist of wryness or mild sarcasm: the bike ride is laden with superlatives, marking the act with strangeness, and the falls down the stairs are “inexplicable,” a feigned ignorance which gestures to a reason that can be explained but not articulated. The satirical nature of the proceedings puts a spin on everything we hear. Everything that happens in that single-sex meeting is by needs relayed to Richard, and while they might accurately describe events, much will be encoded in gendered language and lacuna, the gaps as well as the utterances. Like the Children, the people of Midwich exist in two gendered collectives, and the social conventions are so strong that a lot of information can be conveyed with very little actually said.

The Treatment of Religion

Wyndham uses the characters of Reverend Hubert Leebody and his wife, Dora, to illustrate religious responses to the Children. Mrs. Leebody most easily maps to the curate character in The War of the Worlds, with whom, in one of the stranger interludes in the novel, the unnamed narrator finds himself trapped in a partially collapsed house. While the narrator witnesses the Martians doing truly terrible things from his hidden vantage – the image of the alien sucking the blood of a captured human through a pipette, like a straw, horrifies – he saves much of his fury for his fellow human. The stress of the invasion has driven the curate into a kind of catatonia, alternating between gibbering inaction and hyper-mania. He refers to the Martians as “God’s ministers” (Wells, 71), and understands the attack as a form of divine retribution.[23] This infuriates the narrator – “What good is religion if it collapses under calamity?” (Wells, 71) – and expresses Wells’s own hostility towards organized religion, which he felt deliberately impeded the improvement of humanity under rational and scientific principles.[24]

Similarly, Mrs. Leebody sees her unnatural pregnancy as a form of divine punishment, though she expresses feelings of godly persecution with considerably more restraint. “When things – unusual things like this – suddenly happen to a community there is a reason. I mean, look at the plagues of Egypt, and Sodom and Gomorrah, and that kind of thing.” Immediately in the text, there are three immediate responses: by Zellaby, Zellaby’s pragmatic wife, Angela, and Dora Leebody’s husband, the Vicar.

“For my part,” [Zellaby] observed, “I regard the plagues of Egypt as an unedifying example of celestial bullying; a technique now known as power-politics. As for Sodom” He broke off and subsided as he caught his wife’s eye.

“Er—” said the Vicar, since something seemed to be expected of him. “Er—”

Angela came to his rescue.

“I really don’t think you need worry about that, Mrs. Leebody. Barrenness is, of course, a classical form of curse; but I really can’t remember any instance where retribution took the form of fruitfulness. After all, it scarcely seems reasonable, does it?”

“That would depend on the fruit,” Mrs. Leebody said, darkly (Wyndham, 69).

In addition to being typical of Wyndham’s low-key satirical humor, the three responses to Mrs. Leebody’s feelings of collective punishment are illuminating. Zellaby, as usual, while feeling “impelled to relieve the awkwardness,” only contributes to it by walking right up to talking openly about homosexuality in mixed company. He conceives of religion as a sort of political theater, which he discards as “unedifying.” Her husband, the vicar – much like the curate in The War of the Worlds – ends up sputtering: he has no coherent response to his wife’s feelings of spiritual retribution. It is Angela Zellaby, yet again, who delivers a brusquely reasonable response, one that Dora Leebody dismisses. “I am a sinner, you see. If I had had my child twelve years ago, none of this would have happened. Now I must pay for my sin by bearing a child that is not my husband” (Wyndham, 70). I’m not sure if this circumlocution refers to an abortion, a miscarriage, or simply a desire not to have children, but Dora Leebody nonetheless occupies the position that events are divinely ordained.

Rev. Leebody, while nonetheless tirelessly ministering to the people of Midwich, doesn’t express theological consideration of the Children until near the very end, after the Children have impelled the Pawle brothers to commit suicide. (Honestly, this is a little surprising, given that Leebody is introduced listening to a program on “pre-Sophoclean Conception of the Oedipus Complex,” a title which evinces an obtuse intellectualism more closely aligned with Zellaby’s rhetorical style (Wyndham, 17)). He posits that because the Children are not made in God’s image – God is, apparently, singular, and the Children exist as gendered collective-individuals, to use Zallaby’s term (Wyndham, 117) – they cannot be considered using the same moral yardstick. Despite this theological argument, Leebody nevertheless uses the language of Darwinism. “They have the look of the genus homo, but not the nature. And since they are of another kind, and murder is, by definition, the killing of one of one’s own kind, can the killing of one of them by us be, in fact, murder? It would appear not” (Wyndham, 151). Zellaby sees the implications of this argument straight away: if it is morally permissible for the villagers to kill the Children, then the converse is true. Notably, given his actions in the end, Zellaby rejects this reasoning as “ethically unsatisfactory.” He sees Leebody’s version of God’s likeness as too parochial. “But, as I understand it, your God is a universal God; He is God on all suns and all planets” (Wyndham, 152). Tellingly, Zellaby distances himself from viewing the Children in theological terms – it is “your God”, not his – even when it comes wrapped up in scientific jargon.

By contrast, while the narrator in The War of the Worlds finds the anxious, vituperative morality of the curate infuriating, he ultimately sees the death of the Martians in religious terms. When the Martians are felled by simple bacteria, which he describes as “the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put up on the earth” (Wells, 168), he finds their deaths “incomprehensible.” He only begins to understand their destruction through biblical analogy. “For a moment I believed that the destruction of Sennacherib[25] had been repeated, that God had repented, that the Angel of Death had slain them in the night” (Wells, 169). He ends this epiphany with his hands reaching for the sky, thanking God (Wells, 170). He does downplay this religious exultation later in the epilogue, in a passage which eloquently captures the lingering effect of trauma.

I must confess the stress and danger of the time have left an abiding sense of doubt and insecurity in my mind. I sit in my study writing by lamplight, and suddenly I see again the healing valley below set with writhing flames, and feel the house behind and about me empty and desolate (Wells, 179).

It is in the heat of the crisis that the Wellsian narrator turns to the religion of his childhood. The Martians chose Surrey according to some providential scheme – despite his heated dismissal to the curate earlier – and therefore his suffering has meaningful purpose.[26] Zellaby evinces no such religious framing. While he jokes after the Dayout – during which he and his wife were chilled to the point of hypothermia – about the “underlying soundness of fire-worship” (Wyndham, 57), this isn’t a meaningful religious statement. In the end, Zellaby’s justifications for murdering the Children arise from the brutal logic of evolutionary struggle interpolated into polite society. The threat the Children pose is existential, not rhetorical, or moral. Wyndham very carefully strips out any religious justification for Zellaby’s actions, implicitly or explicitly. There will be no Darwin ex machina.

Welcome to the Jungle

The War of the Worlds ends with more whimper than bang, something that seems to trouble later adaptions. Having the Martian antagonist simply fall over dead serves the point Wells is making about Edwardian colonial complacency or the applicability of Darwinian evolutionary struggle in society, but it isn’t particularly satisfying on a narrative level. The Orson Welles radio play from 1938 – when the world was on the brink of the defining global conflict of the 20th century – punches up the call to arms by the artilleryman, a character the narrator meets in the ruined, empty streets of London. In the novel, the narrator is initially taken by the artilleryman’s rhetoric, which is a fever dream of Darwinian descent, where the survivors will have to “invent a sort of life where men can live and breed, and be sufficiently secure to bring children up” (Wells, 156). They’ll live in the underground and “degenerate into a sort of big, savage rat” (Wells, 157).[27] In the radio play, the artilleryman’s speech is a rousing call to arms; in the novel, the narrator is chagrined to have been susceptible to the man’s “imaginative daring” which, in the cold light of day, seem unhinged (Wells, 158). For Wells, evolution was a force greater than his Martian invaders. While his characters may conceptualize the war between the worlds as a religious, moral, or ethical struggle, the simple unalterable fact is that the true struggle occurs outside of conscious thought, on a biological level. “With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter” (Wells, 7).

Wyndham’s take on the alien invasion neatly reverses the action of Wells’s novel. While it may end on a literal bang, the invasion itself is submerged under – to quote a snarling contemporary review – “layers of polite restraint, sentimentality, lethargy and women’s-magazine masochism.”[28] There are no heat rays or chaotic retreats, no monstrous antagonists. The invasion occurs within the confines of the domestic, and its focus is a group of children who are, from the very first, defined in military terms and as a racially constructed other.[29] If indeed the Children are the next iteration of humanity, as Zellaby posits (Wyndham, 197), then there is no rational reason not to step aside and let nature take its course. In Wells’s narrative, the Darwinian struggle is both inexorable and outside of conscious control. In The Midwich Cuckoos, by defining the Children as evolutionary antagonists, Zellaby positions himself as an agent of evolution. The Children must die so his children can live.

Zellaby describes his final act as a “heroic sacrifice” (Wyndham, 212), and Wyndham is careful remove any moral objections but the most glaringly obvious one: the premeditated murder of children by a suicide bomber.[30] None of these children are either his own or his grandchildren – his own wife was already pregnant during the Dayout, and his daughter’s cuckoo child one of three who died of influenza (Wyndham, 110). He himself has “a matter of a few weeks to live” (Wyndham, 212), and he takes pains to ensure only he and the Children will be killed in the blast. In a purely intellectual way, this is an elegant (final) solution to the Gordian knot the novel has twisted itself into. The Children themselves (assuming, for the moment, the usual role of Dr. Zellaby), while talking to Bernard, describe the political gridlock which will ensue should the perceived threat of the Children become more widely known. Even if parliament could be roused to contemplate annihilating the Children, “what government in this country could survive such a massacre of innocents on the grounds of expediency?” (Wyndham, 193). Immediately preceding their destruction, Wyndham takes a moment to remind you forcefully that these are still children. The narrator observes, as the Children remove AV equipment from Zellaby’s car:

There was nothing odd or mysterious about the Children now unless it was the suggestion of musical-comedy chorus work given by their similarity. For the first time since my return I was able to appreciate that the Children had ‘a small ‘c,’ too’” (Wyndham, 208).

The chapter heading here is “Zellaby of Macedon.” The most famous leader from Macedonia was, of course, Alexander the Great, who amassed one of the largest empires in antiquity during his short reign. He is also known for cutting the Gordian knot – or solving an intractable problem by bypassing the perceived constraints of the problem. Zellaby solves the problem posed by the Children by personally acting against them, thus bypassing all the thorny issues of societal or governmental ethics. Yet again, Wyndham is using his subtle satire to undercut Zellaby. Aligning Zellaby with Alexander the Great seems highfalutin and shows off one’s classical education, but when you get right down to it, the appellation “Zellaby of Macedon” is ridiculous. A sick old man is not comparable to one of the greatest generals of antiquity. This is in line with the treatment of Zellaby throughout the text: Zellaby looks like the authorial mouthpiece, but there’s a twist to his portrayal.

The final epigraph – Si fueris Romae, Romani vivito more – which is typically translated as “When in Rome, do as the Romans do” is instead parsed as “If you want to keep alive in the jungle, you must live as the jungle does….” Zellaby neatly inverts the meaning of the phrase, which is originally about operating within spaces of different cultural rules and expectations by those rules and expectations. Peeling back the artifact of society reveals the more “fundamental expression,” to use Zellaby’s phrasing: brute, biological survival (Wyndham, 213). That the ending invokes the jungle after the events of a novel which could comfortably be described as a comedy of manners feels jarring, just as jarring as a verbally circumambulatory philosopher calculatingly suicide-bombing a classroom full of children. The Children are strange and often uncanny, but not obviously so. They are gestated and born to human mothers; they can be carried off by flu or killed in car accidents; they like sweets and movies like other children. They have what Wells called the “human likeness” when ironically discussing the British destruction of indigenous people (Wells, 9). The acts of violence attributable to them are exclusively reflexive: they respond to attack with an aggressive defense. When one of the girls discusses how they will supersede humanity in the end, it is in terms of biological superiority, not wholesale annihilation. When their destruction by the British seems imminent, their response is to try to flee. Their danger to humanity is only inferred or imagined in the context of Darwinian struggle. As Zellaby says, “[The Children’s] immediate concern is to survive, in order, eventually, to dominate” (Wyndham, 199). If one’s simple existence is couched in terms of existential struggle, the final, genocidal act in The Midwich Cuckoos, perpetrated by an avuncular figure against a classroom full of children, becomes inevitable.

[1] John Wyndham, The Midwich Cuckoos (New York: Modern Library, 2022), 29-30, 40. All subsequent references are to this edition and are noted parenthetically in the text.

[2] H. G. Wells, The War of the Worlds, ed. Patrick Parrinder (New York, NY: Penguin, 2005), 7. All subsequent references are to this edition and are noted parenthetically in the text.

[3] Adam Roberts, The History of Science Fiction (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 310-312.

[4] McLean details how Wells dismantles Spenser’s Darwinism. See Steven McLean, “The Descent of Mars: Evolution and Ethics in The War of the Worlds,” in The Early Fiction of H. G. Wells: Fantasies of Science (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp. 89-113, 98.

[5] Their philosophical disagreement is, of course, considerably more complicated than what is written here. See Klára Netíková, “T. H. Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics: Struggle for Survival and Society,” E-LOGOS 26, no. 1 (2019): pp. 4-18, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.e-logos.460, 4-7.

[6] Paul K. Alkon, Science Fiction Before 1900: Imagination Discovers Technology (New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, 1994), 48.

[7] In one bizarre instance, one of his novels, The Outward Urge, is attributed to not one but two pen names: John Wyndham and Lucas Parkes. For description of the publishing history see Amy Binns, Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters (Hebden Bridge, UK: Grace Judson Press, 2019), 220.

[8] Brian W. Aldiss, Billion Year Spree (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973). 290.

[9] Amy Binns, Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters (Hebden Bridge, UK: Grace Judson Press, 2019), 108-111.

[10] The titular triffids are exactly this. John Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids (New York, NY: The Modern Library, 2022).

[11] The alien antagonists of The Kraken Wakes are deep sea creatures who wage war literally on earth. John Wyndham, The Kraken Wakes (New York, NY: Modern Library, 2022).

[12] Damon Knight, In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction (Chicago, IL: Advent Publishers, 1974), 178.

[13] Adam Roberts, The History of Science Fiction (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 310-312.

[14] The appendix to the Penguin edition includes several maps where you can follow the action of the novel, in addition to annotation of the locales mentioned. H. G. Wells and Andy Sawyer, “Appendix: Note on Places in the Novel,” in The War of the Worlds (London, UK: Penguin Classics, 2018), pp. 181-185.

[15] Howard Koch, Orson Welles, and H. G. Wells, “Mercury Theatre on the Air: War of the Worlds,” Indiana University Bloomington (Indiana University, 2017), https://orsonwelles.indiana.edu/items/show/1972.

[16] My grandfather, G. Edward Busch, was 31 at the time of the broadcast, unmarried, and still living with his parents in Pennsylvania, which wasn’t that far from the invasion site in New Jersey. He returned home from work to find his parents very upset by the broadcast. As both a scientist and a dramatist, Ed was a keen fan of Orson Welles, and assured them the broadcast was during the Mercury Theatre hour, and that the country was not being invaded. There is dispute about how many people took this broadcast seriously, but family lore, at least, suggests it was, albeit provisionally. For a discussion of the panic from the man who wrote the script for the radio play, see Howard Koch, The Panic Broadcast: Portrait of an Event (New York, NY: Avon, 1970).

[17] Károly Pintér, “The Analogical Alien: Constructing and Construing Extraterrestrial Invasion in Wells’s ‘The War of the Worlds.’ ,” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) 18, no. 1/2 (2012): pp. 133-149, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43488465, 137.

[18] For in depth psychoanalytic analysis of the Children of Midwich, see Steven Bruhm, “The Global Village of the Damned: A Counter-Narrative for the Post-War Child,” Narrative 24, no. 2 (May 2016): pp. 156-173, https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2016.0013.

[19] Damon Knight, In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction (Chicago, IL: Advent Publishers, 1974), 253.

[20] Károly Pintér, “The Analogical Alien: Constructing and Construing Extraterrestrial Invasion in Wells’s ‘The War of the Worlds,’” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) 18, no. 1/2 (2012): pp. 133-149, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43488465, 137.

[21] Wells scholar Patrick Parrinder addresses the many ways the narrator of The War of the Worlds is ultimately untrustworthy, especially about the Martians. Patrick Parrinder, “How Far Can We Trust the Narrator of ‘The War of the Worlds,’” Foundation 28 (1999): pp. 15-24, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/how-far-can-we-trust-narrator-war-worlds/docview/1312028428/se-2.

[22] Patrick Parrinder, “How Far Can We Trust the Narrator of ‘The War of the Worlds,’” Foundation 28 (1999): pp. 15-24, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/how-far-can-we-trust-narrator-war-worlds/docview/1312028428/se-2, 16-18.

[23] Denis Gailor, “‘Wells’s War of the Worlds’, the ‘Invasion Story’ and Victorian Moralism,” Critical Survey 8, no. 3 (1996): pp. 270-276, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41556021, 273.

[24] S. J. James, “Witnessing the End of the World: H.G. Wells’ Educational Apocalypses,” Literature and Theology 26, no. 4 (December 21, 2012): pp. 459-473, https://doi.org/10.1093/litthe/frs052, 461-462.

[25] This refers to the biblical account of the historical Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC by Assyrian king Sennacherib described in 2 Kings 18–19 and Isaiah 36–37

[26] Patrick Parrinder, “How Far Can We Trust the Narrator of ‘The War of the Worlds,’” Foundation 28 (1999): pp. 15-24, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/how-far-can-we-trust-narrator-war-worlds/docview/1312028428/se-2, 23.

[27] This scenario is what more or less plays out in Wells’s The Time Machine, which was published two years previous to The War of the Worlds. H. G. Wells, The Time Machine, ed. Patrick Parrinder (New York, NY: Penguin, 2005).

[28] Damon Knight, In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction (Chicago, IL: Advent Publishers, 1974), 254.

[29] Adam Roberts, The History of Science Fiction (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 311.

[30] David Ketterer, “‘A Part of the … Family [?]’: John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos as Estranged Autobiography,” in Learning from Other Worlds: Estrangement, Cognition, and the Politics of Science Fiction and Utopia, ed. Patrick Parrinder (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), pp. 146-177, 165.