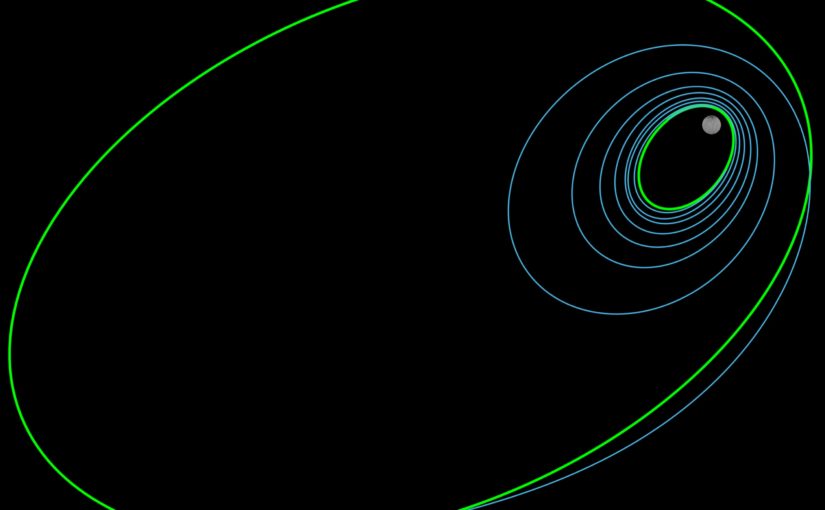

In the end, the zombie apocalypse was nothing more than a waste disposal problem. Burn them in giant ovens? Bad optics. Bury them in landfill sites? The first attempt created acres of twitching, roiling mud. The acceptable answer is to jettison the millions of immortal automatons into orbit.

Horror can seem a little rule-bound at times. There’s a monster, say a zombie. You work out how it’s defined – it’s a living person infected with a rage virus, or a dead person who is reanimated. It can run, or it can’t. It can climb, or it can’t. It doesn’t like sunlight or it doesn’t care. You figure how to kill it, or immobilize it, or cure it, or you die and join it. You figure out if everyone is infected, or if it’s transmissible, or how long it’s been since the first outbreak, the last outbreak. You set up communities that function according to rules that dovetail into the rules for the monster. In this way, you make the point that the true monster is human. Ba dump tss.

The opening of The n-Body Problem by Tony Burgess, despite a seriously questionable level of sanity from the first person protagonist, seems to start with rules in mind. It’s been 20 something years since the first dead person didn’t stay dead. It’s not so much that they became flesh-eating corpses, but that the dead just never stop moving. After the initial panic died down, they had millions of wriggling undead bodies to be disposed of. End result: they start shooting them into space. Our protagonist – who I would like to note is off his nut – is spending his time plying some serious hypochondria and chasing a man called Dixon. Dixon is a traveling horror show who rolls into town and convinces the entire town to kill itself, presumably so they can go to space because it’s so pretty and peaceful up there. Then he plays in their corpses.

You can kinda see how this set up might unfold: the requisite show down between Dixon and Bob (which is not the protagonist’s name, but I think the only one he ever gives); the boy Bob picks up serving as a generational example of What Has Changed; some pyrotechnics with WasteCorp, which is the multinational company that has shot a billion wriggling corpses into space; maybe even a sequence in the cold airlessness of space, the sun rising over the black orb of the planet in wavering stabs of light. Burgess occasionally gives you glimpses of these narrative possibilities – like a searing fever dream that takes place in space, the corpses turning sunward like flowers – but mostly he just laughs inscrutably and delivers some of the sickest shit and stomach-dropping plot turns I’ve ever seen.

The n-body problem is a mathematical problem going back to antiquity for predicting the motions of celestial objects in gravitational relationship with one another. This is certainly a problem if you don’t understand that, say, the stars and planets are not in a fixed orb rotating around the earth, but it’s apparently also difficult to solve using general relativity. Frankly, there’s a lot of wonky maths that I don’t get in the explanation. Obviously, this book is named The n-Body Problem because of one billion corpses in space and all that, but I think there might be another reason too: Burgess is taking a big, gory dump on post-apocalyptic conventions, just absolutely hazing you and your expectations. Solve for x, bitch.

Another possible title for this novel: Trigger Warning for All Things.

So you want to see some marauding cannibals and rape gangs? Boom, only he turns the rape gangs into a mordant joke, and denies you the prurient thrills that so much apocalit delivers in the form of sexual assault. How about a blood bath? Boom, only this time it’s a swimming pool, and the blood is still shimmering in that uncanny way of the undead here. The sickness is so sick it’s downright funny at times, these horrible laundry lists of horrors that numb until, wait, what the holy hell was that? The whole thing is completely bonkers, transgressive in a way that goes beyond the usual transgression of body horror, of which there is plenty. Nobody’s going to yell, “Oh, the humanity!” when the zombies start falling from the sky in some half-assed coda.

“They look like cherry blossoms. Opening and then falling apart in the wind.”

I guess I could go on, but I’d probably get into spoiler territory. I just want to note, quickly, that there’s something here that reminds me of Ice by Anna Kavin. Ice is a strange, mid-century post-apocalyptic novel written by a functioning heroin addict which is about, insofar it is about anything so easily spoken, two men fighting over girl. The landscapes rear up in the same ways, the connectives cut with a box-cutter, the identities fragile and mutable. And the ice. Ice made me incredibly uncomfortable – often in ways The n-Body Problem does not, owing to certain perversions I have about mid-century novels – but there’s still a central discomfort that feels the same to me. This discomfort doesn’t necessarily come from content – though, I did mention this was sick, non?- but some deeper, more chthonic level which implicates me in the proceedings. If I were still rating things – I’m trying not to – I’d leave this similarly unrated, because no metric as childish as stars – their motions cannot be solved for anyway – can get at my response.

So yeah, thanks to sj for turning me onto this, but then also what the fuck did I just read?