Note: I wrote this for the B&N SciFi & Fantasy blog in 2018 and it was one of my favorite pieces I wrote for them. They’ve inexplicably taken it down, so I’m putting it back up.

I’ve long referred to Ursula K. Le Guin my literary grandmother, a polestar of my understanding of fiction, fantasy, and the world itself. When I learned of her death earlier this year, I sat down and cried. Even though she passed at the respectable age of 88, I cried long, wracking tears. She is the writer I found at that specific age when I wasn’t so young that I barnacled and burnished her fiction with the obscuring mist of nostalgia, nor was I too weary and worldly to be above young adult books like A Wizard of Earthsea. Indeed, her work has kept me from succumbing to the fallacy that I will ever be too important to read books about that terrifying time between childhood and the adult world.

If you have read an Ursula K. Le Guin novel, likely it is A Wizard of Earthsea, or perhaps The Left Hand of Darkness or The Dispossessed. But she wrote so many more books than those. She wasn’t as prolific as some science fiction and fantasy authors, but she filled a career of five decades with remarkable works that will long outlive her. Though weighing one book against another is always a personal process—and so many of Le Guin’s books are so, so personal to me—still I have endeavored below to place them in an order that makes a kind of emotional sense. It does to me, anyway. Hopefully to you too. Regardless, Le Guin’s body of work is a well that will sustain you, if you only drink from it. So drink. Drink long, and drink deep.

And so, from merely worthwhile to the most essential: a ranking of the novels of Ursula K. Le Guin.

Very Far Away From Anywhere Else

This slender young adult novel, written in 1976, doesn’t have anything wrong with it exactly, but it sure hasn’t aged well in the intervening 40-odd years. Owen Griffiths is a misunderstood teen—too smart, too weird, too short. He’s made peace with his differences, much to the chagrin and disappointment of his crushingly normal parents, and is working doggedly toward attending either Cal Tech or MIT. He’s going to get out of this town, this life, this normalcy. But he’s still a teenage boy, and when he strikes up a friendship, and then something more than friendship with his neighbor, Natalie Fields, he’s got to deal with the both completely usual and totally disordering effects of young love. Very Far Away from Anywhere Else is a very sweet novel, with some bright patches of keen observation. Unfortunately, it feels so dated now as to read like a period piece, something like the (pun so intended) menstrual belts in Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret? but without the more relatable aspects of that novel.

Rocannon’s World

I have a fair amount of affection for this, Le Guin’s first published novel, but even I can admit it’s a mess. It was written as a postscript to the short story, “Semley’s Necklace,” which detailed and dispatched a fairly simple SFnal scenario involving both first contact and the time dilation effects of interstellar travel. After the events of “Semley’s Necklace,” the Hainish ethnologist Rocannon returns to her planet, and meets no less than four sentient species in his quest. There are flying mounts who must look like lions with wings, bestial creatures who look like angels, people who live underground like trolls, medieval-ish societies, and so, so much more packed into this short novel. Like I said, a mess. But it’s here Le Guin coined the term ansible—a device capable of instantaneous communication across the galactic void—and introduced us to the Hainish, the far-ranging culture we encounter in many of her novels. The ansible will become the lynch pin in her Hainish books, one of her broadest and most important canvasses.

City of Illusions

Another early Hainish novel, City of Illusions is the third published in that series. Its main character is a descendant of the people of Planet of Exile, but generations hence, on an Earth (or Terra, if you will) taken over and controlled by an alien protagonist called the Shing. Falk wakes up with no memories in a small, rural community of occupied Terra. Through his questing, his memories of his other self, Agad Ramarren, are recovered, and his Falk-self subsumed, until both can come to an equilibrium. Like Rocannon’s World, City of Illusions is pretty messy, with philosophy of the mind wrestling with the precepts of Taoism in a classic dystopia. The Lathe of Heaven ended up exploring these themes much more adroitly. That said, the descriptions of an earth re-growing after an apocalypse in a distant past are beautiful in their strange way, a post-apocalyptic pastoral.

The Beginning Place

The Beginning Place is another early oddment, about two young people somewhere in that liminal period between childhood and adulthood. Irene Pannis and Hugh Rogers both have small, mean lives in an unnamed American city. Both begin escaping to idyllic Tembreabrezi, a Narnian fantasy land. Irene has been coming to Tembreabrezi long enough to learn the language and culture, and initially views Hugh as an interloper. When a sickness of fear strikes the simple folk of this other land, Hugh and Irene set out together on an old-fashioned quest to kill the beast, which stands in harsh contrast with the intractable problems of their real lives; if only rent could be slain like a dragon. Sometimes people read escapist fiction because they have something to escape from. Le Guin twists escapism and realism in The Beginning Place, which is an uncomfortable thing to do.

Planet of Exile

During my research, I learned that Planet of Exile was often published together in something called the tête-bêche format with a Thomas A. Disch novel. (Now that’s something you know!) Planet of Exile follows Terran settlers on a planet called Werel. Werel has an orbital period of 60 Earth years, which means its winter lasts something like 15 of our years. (George Martin, eat your heart out.) We’re introduced to our Terran colonists at the beginning of this long winter, as they try semi-successfully to integrate into the indigenous population. While both the Werelians and Terrans appear to be descendants of Hainish settlers, there’s been too much genetic deviation, and the two populations can’t intermingle successfully. Planet of Exile both critiques and props up the anthropological model of contact with indigenous people. Because of Le Guin’s upbringing as the child of famous anthropologists, this is a concern that resonates through much of her work.

The Telling

I feel like a jerk for listing so many of Le Guin’s Hainish novels in the bottom dozen of this list, but the Hainish novels constitute a huge part of her catalog, so maybe it’s just statistics. Despite the tenuous threads linking one Hainish novel to another, most of them feel standalone, and Le Guin never did much fuss with strict continuity. That said, The Telling feels apart from the the other Hainish novels, off in an eddy. Sutty, an Anglo-Indian Ekumen observer, is sent to the planet of Aka. Aka’s indigenous cultural expression is called the Telling, which, like the Tao or Confucianism, is a practice more than a religion, a folklore more than a mythology, but nevertheless deeply ingrained. The autocracy of Aka has outlawed the Telling, and Sutty dodges her government minder while trying to immerse herself in this forbidden lore.

Voices

Voices is the second novel in The Annals of the Western Shore, one of Le Guin’s young adult series. The novel follows Memer, who lives in the city Ansul. Ansul is an occupied city, and Memer herself is a “siege brat,” the daughter of an Ald soldier who raped her mother early in the Ald’s conquest of the city. Like all of the Western Shore novels, Voices takes on very serious issues, especially for a book ostensibly aimed at the young adult. (But then Le Guin never viewed writing for the young as a lesser form of writing, or watered down writing for adults.) Le Guin does not vilify the occupying Ald, nor romanticize the people of Ansul overmuch; this is not a simple tale of overlords and resistance written in black and white. She deals quite seriously with the conflict between a monotheistic society and a polytheistic one, and the inequities of a society both broken and built by violence. Still, there is something arm’s length about Voices. I feel like it is better considered than felt, more structural than emotional. Certainly, a reader with other predilections might sort this novel higher, but for me, I feel like the other novels in the series strike a better balance between heart and head.

The Word for World Is Forest

The Word for World Is Forest is the closest thing to a polemic Le Guin ever wrote. Written at the height of the Vietnam War, it is set on forest world of Athshe, which has been colonized by the resource-hungry Terra. (Terra is Earth; this is another Hainish novel.) The indigenous people of Athshe have been enslaved to help the Terrans deforest their world. Athsheans practice something like lucid dreaming, but on a collective scale: they all dream together. When the Athshean Selver’s wife is raped and murdered by a colonial commander named Davidson, he wakes up, in a sense, learning to resist the Terran conquerors, sometimes by violence. He tells Davidson at one point that Davidson has given him the gift of murder. (When James Cameron’s Avatar was released, the comparisons with The Word for World is Forest were inescapable.) In this novel, Le Guin’s anger is very close to the surface: for the cruelty of colonization, the pillaging of the natural world, the treatment of people as resources.

The Eye of the Heron

The Eye of the Heron follows the conflict between two groups of Terran settlers on an otherwise unpeopled world. One group is the descendants of a penal colony, and the other the children of pacifist political dissenters. The pacifists, who are largely farmers, are planning on starting another farming community further inland. The other group, who see themselves as the oligarchical rulers of the planet, are unwilling to let people they see as subject go. The Eye of the Heron feels very shocking because (spoiler) halfway through, the pacifists’ hero figure is dead in the street, killed by oligarchs. Le Guin wrote later about this death:

“While I was writing The Eye of the Heron in 1977, the hero insisted on destroying himself before the middle of the book. “Hey,” I said, “you can’t do that, you’re the hero. Where’s my book?” I stopped writing. The book had a woman in it, but I didn’t know how to write about women. […] It taught me that I didn’t have to write like an honorary man anymore, that I could write like a woman, and feel liberated in doing so.”

Le Guin is rightly lauded as a feminist writer who wrote sensitively about gender, but her career started way back when; her early novels were written back before women were invented (to use Le Guin’s own comic phrasing on the matter). The Eye of the Heron is a turning point for her, opening up the narrative possibilities of writing about the concerns of women. It also touches on themes, like the practice of non-violence, that will come to full fruition in her most influential works, novels like The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness.

Searoad

Searoad is one of three short story collections I’ve included in this ranking, as I believe they constitute a novel-in-stories: shorter narratives tied so tightly thematically or geographically (or both) that they read like a novel. Like Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson, which is an early exemplar of this form, Searoad takes place in a single locale: the fictional seaside town of Klatsand, Oregon. The stories largely focus on the lives of women in this tourist economy, and involve multiple generations of the town’s citizens over decades. Though Le Guin is primarily known as an SFF writer, Searoad is one of many of her fictions that defy that label. My favorite story here is about the proprietor of a run-down motel who naps in the unoccupied rooms, sleeping away the time she always means to use improving the property. Her inadvertent eavesdropping on a young man sobbing out an unknown grief in an adjoining room completely slayed me. This may give you an indication of how melancholic and glancing these stories are, focused so keenly on the everyday, but dreaming larger.

Powers

Even though Powers was awarded the Nebula (which is, along with the Hugo, one of the two most prestigious SFF awards in the States) for best novel in 2009, I don’t think it’s the best of the three novels in The Annals of the Western Shore. (That was a weird year for the Nebula; despite the establishment of the Andre Norton Award for Young Adult novels two years prior, two of the six nominated works for best novel were young adult novels: Powers, and Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother.) Powers follows Gavir, a young man and slave who is trained to be teacher and tutor to the noble family who owns him. His upbringing is quiet and insulated, almost bucolic; his owners are “the good kind” (never mind that there is no good kind of slaver). It is only after the brutal murder of one of his fellow slaves that he understands the true parameters of his inequity. He escapes to a hard wandering in the wilderness. Powers tackles necessary and vital themes, and Le Guin is as the height of her powers as a wordsmith.

The Farthest Shore

The Farthest Shore is the third in the original trilogy of Earthsea novels Le Guin wrote, one after the other, in the late ’60s and early ’70s. They are all set on an archipelago of islands in a vast, uncharted sea, in a place with magic, dragons, and wizards. Each novel at least touches on the life of Ged, who becomes the arch-mage of all of Earthsea, though he’s not always the protagonist. Earthsea is a place with a word-magic, where if you can speak the true name of a thing, you can influence that thing. At the beginning of The Farthest Shore, there’s a malaise on Earthsea: not only is magic faltering, but even non-magical crafts are suddenly forgotten, even by the most adept. The archmage Ged leaves his seat of power on Roke Island, and travels with a minor prince, Arren, who came to Roke first to plead for his people in these devastating times. Magic in Earthsea is dying because a sorcerer has sought to kill death and become immortal. This throws off the entire equilibrium of islands, one Ged and the boy who will be king must reestablish. The Farthest Shore is a beautiful and fitting conclusion of the original Earthsea trilogy. It is also so, so sad.

Lavinia

Lavinia is something of an oddity in Le Guin’s career. It can’t rightly be called fantasy or science fiction. It’s not one of her Orsinian Tales either, set in a central European country of her own devising, but nevertheless in a recognizable European history. Lavinia is fairy tale, of sorts, but grounded in the prosaic; a story of a simple life lived in the margins of epic poetry and the national founding myth. Lavinia is the story of Aeneas’ second wife, a princess of Latinum, with whom he was prophesied to start an empire. In Virgil’s Aeneid, she doesn’t utter a word. In that lacuna, Le Guin tells the story of a devout daughter of her homeland, married off to a warlord. But Lavinia’s marriage to the scarred Aeneas, hero of the Trojan war, is strangely soft and tender, and so much more sweet for its brevity. I’m not ashamed to admit I burst into tears at the end of this novel, though I couldn’t tell you rightly why. There’s a slip there, in the end, from the lived life to the mythic, and so much is both lost and gained in that transmutation. Lavinia is a strange novel, to be sure, with a sense of day to day life that’s often missing from myth, even while it stretches its dark wings and soars into the mythopoeic.

Malafrena

Malafrena is the only novel-length narrative in Le Guin’s Orsinian stories, which take place in an invented central European country over the last century and a half. (The name of the country, Orsinia, is something of a joke: Le Guin’s first name, Ursula, means bear, and Orsinia takes its name from the same word roots; it is Le Guin’s own country.) Malafrena follows Itale Sorde from his bucolic beginnings on the eponymous lake Malafrena, out into revolutionary politics of the capital, and then back again to his humble beginnings. “True journey is return,” she wrote in contemporaneous journals. When the Library of America sought to publish Le Guin’s works—a serious literary honor—they began with her Orsinian stories, at her behest. To me, Malafrena feels old school, like an expert ventriloquism of late 19th Century and early Modernist novels, from its concerns to its historical situation. It’s good, but it’s not good in the ways Le Guin is good when she’s writing in the worlds she creates herself. It’s funny that a country she named for herself doesn’t feel quite like it’s written in her voice.

Gifts

Gifts is the first of The Annals of the Western Shore. The novel follows two young people, Gry and Orrec, who live in an insular and somewhat backward region, the kind of place where grudges are nursed for generations against neighbors. The family groups in the area also have hereditary powers, which are exulted. Orrec is blindfolded at the fairly late adolescent discovery of his gift, forced to live without his sight, due to his father’s insistence that his wild gift of “unmaking” is simply too lethal to allow. That this wild gift coincidentally aligns with his father’s petty concerns that Orrec has dangerous gifts (or is known to have dangerous gifts) is well more important than Orrec’s sight. Gry is the daughter of a neighboring hold with which Orrec’s family is often violently feuding; her gifts involve a communication with animals, one she refuses to use for hunting, to the irritation of her people. Orrec and Gry come of age in a small, mean, vituperative community, and struggle to live with gifts that seem like anything but. Their relationship is tense and sweet, both difficult and easy, and their rough world is richly drawn.

Four Ways to Forgiveness

Four Ways to Forgiveness is written as four interlinking novellas that concern the planets of Werel and Yeowe. (The planet that is the setting for Planet of Exile and City of Illusion is also called Werel, but they are not the same place; Le Guin simply forgot she’d already used the name in novels written decades previous.) The largest government on Werel, Voe Deo, practices a form of chattel slavery, even into an industrial revolution where the slaves become known as “assets”, leased out to the factories. Voe Deo also uses its slave population to colonize the otherwise uninhabited planet of Yeowe. The stories in Four Ways to Forgiveness largely center on the period when Yeowe began its fight for independence (and the larger abolition of slavery) and the period directly after, when the people of both Werel and Yeowe have to learn how to live without slavery. Though there’s something hopeful about these narratives—they are “ways to forgiveness” in the end—these are uneasy stories about deeply traumatized people. It’s a way to forgiveness, but not the end.

The Other Wind

The Other Wind is the last of the Earthsea stories. The first three, written altogether in the late ’60s and early ’70s, share a certain narrative unity. Le Guin returned to Earthsea in the 1990s with Tehanu, which she called, at the time, the “last book of Earthsea.” As it turns out, Earthsea wasn’t done with her, and she wrote two more books in the world: Tales from Earthsea, a collection of short stories that deepens the lore of the history of magic, and The Other Wind. The Other Wind comes to terms with and explodes a number of fantasy conventions. A simple man named Alder, who is adept at mending, is visited by his late wife in dream. She seeks to tear down the wall between the living and the dead in his dreams, but in ways that seem to alter his living life. He seeks out the former archmage, Ged, who poured out his power in The Farthest Shore, and is now just a man, and Lebannen, who is now king. Like most of the Earthsea stories, The Other Wind is story of a journey, both on the water, and into the self.

A Guardian review written at the time of its publication said it best: “Gradually, in a masterpiece of chilling narration, the whole living world becomes unable to sleep. And to fix that, the world has to become like our own, to become like our un-magical selves: to grow up.” The Other Wind is a strange, sad, melancholic narrative about childhood’s end, and the exhilarating possibilities of death’s revival. It’s a young adult novel that drops the young, which hurts an exhilarates as much as that always does.

Changing Planes

Changing Planes is another novel-in-stories, where a collection of shorter stories feels like a novel. Changing Planes feels especially novel-esque because it’s a frame narrative, where an introductory story is told to set the stage for other stories that exist somehow within that framing device. (A widely known frame narrative, one that many of us encountered in middle school, is Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: the folk on a pilgrimage in 14th C. England tell each other stories.) The frame in Changing Planes is based on a pun in the story “Sita Dulip’s Method.” Sita discovers that the boredom, discomfort, and low grade anxiety produced by the forced inactivity when you’re changing planes (or otherwise stuck in waiting rooms) can cause a person to change planes of reality. A myriad of other worlds open up to the casual traveler. Some of the stories about these other worlds are in the vein of ethnographic studies; others are deeper dives into lives lived. Every world Le Guin details in this collection could easily be a stage for an entire novel, or series of novels. Instead, she gives us this this almost casually masterful collection of thought experiments and cool ideas, a waiting room that opens to a larger world of imagination.

Always Coming Home

It’s generally true that when an author writes about their hometown, what they end up saying has a strange, hard to define depth. Though Le Guin is strongly associated, as a writer, with the Pacific Northwest—she made her home both fictionally and in reality in the temperate rainforests of Oregon—she’s a California girl, born and raised. (Fun fact: Le Guin and Philip K. Dick both graduated from Berkeley high school in 1947, though they never interacted.) The setting of Always Coming Home is a California peopled by the peaceable Kesh, who “might be going to have lived a long, long time from now.” The first half follows Stone Telling, a daughter of a Kesh mother and a father from the more rigid, expansionist Dayao. The second half is the field journal of an ethnographer called Pandora who describes the culture of the Kesh through poems, stories, recipes, site maps, and even music. (Some early editions included a cassette tape of this music in a box set.) As befits the strange future/past tense of the novel, this California feels like a post-apocalyptic pastoral, taking place generations past modernity in a place aware of such a thing, but not beholden to it; modern America is just another set of folk stories.

Many years ago I had a conversation with a fellow Ursine devotee, and he called Always Coming Home her most deeply felt work. I was surprised by that at the time; this is not a novel one sinks into. I have since come to understand what he meant, and wholeheartedly agree. The sense of retrospective—the way both halves of the novel turn back to consider a childhood (in Stone Telling’s narrative) and the larger cultural milieu (in Pandora’s notes)—feels like Le Guin considering her own childhood using the cultural tools she learned during that childhood. Her parents were both well-regarded anthropologists, and there are strong similarities between the Kesh and the Native American myths and history recorded by her parents. Her childhood, and its Northern California setting, therefore exist in a half-place, something like a mythic past that that nonetheless tells tales of contemporary America. It is considered at something closer than arm’s length, and further than memoir. Always Coming Home doesn’t hew to anything like a traditional narrative structure; it is more like the cultural detritus we all haul with us out of our home towns, laid out with the most careful hand.

Tehanu

The three original Earthsea novels are the kind of young adult stories at which fantasy literature excels, set in a pre-industrial place where people have all the trouble of growing up, without all the ornament of modern life to molder and grow dated as the fiction ages. Two decades later, Le Guin returned to Earthsea, and found it changed, as she had changed as a writer. Tehanu finds Tenar, the once child priestess from The Tombs of Atuan, now living a quiet life as a solitary grandmother on Gont, the childhood home of the archmage Ged. Tenar has taken in the child Therru, who was sexually assaulted and nearly burned to death by her father and the vagabond band she was born into. Therru is treated as bad luck and bad omen: the lore of Gont maintains that the damaged deserve their bad luck; that is how they came to be damaged. Worse, bad luck can be catching.

Tenar and Therru travel to see the wizard Ogion on his deathbed, and there intersect with Ged, once archmage, who has poured his power out to seal the breach between life and death in The Farthest Shore. Ged and Tenar renew their acquaintance, which was begun so, so long ago, and deepens to something more. Ged is deeply traumatized by the loss of his powers, and Tenar gives him room to grieve. All of the principle characters of Tehanu are hurt in some way, struggling to rebuild lives that have been burnt to ashes. The ending, where Tenar, Ged, and the child Therru must confront the violence that has so changed their lives, is exultant: a beautiful, burning awaking of Therru’s true nature. Tehanu doesn’t feel much like a young adult novel—it’s too grim, and too violent in places—but its earnest, heartfelt, and soaring portraiture of a burned child coming into her fiery power feels like a necessary tale for both the young and the old.

The Left Hand of Darkness

Published first in 1969, The Left Hand of Darkness was a stunning novel at the time. Genly Ai, an envoy for a loose galactic confederation called the Ekumen, is sent to the icy planet of Gethen as something between an ambassador and an anthropologist. The people on Gethen are ambisexual: at their times of sexual fertility, their bodies shift to one sex or the other, but otherwise they have no fixed sex. They are unique in the known worlds in this way. Genly Ai’s primary relationship is with Estraven, the prime minister of the constitutional monarchy of Karhide, the country that Genly is embedded within. Interstellar travel and the concept of extra-Gethenian humans seem unbelievable to the Gethenians; Genly is seen as either a slightly mad curiosity or a dangerous disruption. Due to Genly’s Terran ideas of masculinity, his distrust of Estraven’s mercurial sexuality, and his misunderstanding of the cultural practice of shifgrethor (which is something like a code of conduct more instinctual than codified), his sojourn in Karhide is near-disastrous. Estraven makes very real sacrifices for Genly in their halting, political, and personal relationship, one colored by both the conflict of empires and the simple mis/understanding of two people. Ultimately, the other envoys from the Ekumen kept in stasis above the planet are allowed to awaken and speak for the Ekumen’s goals.

In the intervening decades, aspects of The Left Hand of Darkness have become antiquated or essentialist—Le Guin herself first somewhat defensively justified her use of the default pronoun “he” for all Gethenians, but later acknowledged that “he” need not be the default. Overall, the ways the novel grounds itself in character study keeps it from being a period piece, read for its important contribution to SFF, and not because it’s a relatable novel. When the members of the Ekumenical team touch down on Gethen, their binary sexuality seems so remarkable to Genly, who has spend the whole novel struggling with Gethenian ambisexuality. Le Guin does such a good job of immersing you (and Genly) in fluid sexuality of the Gethenians that the intrusion, at the end, of people who embody a sexual binary seems truly strange.

The Dispossessed

Le Guin’s Hainish novels are all bound together by a specific technology (a plot device, if you will): the ansible, an invention that allows instantaneous communication across interstellar distance. The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia tells the story of the ansible’s invention, by the physicist Shevek. The novel also, as its subtitle indicates, takes on the interactions of various political systems. The setting is the planet Urras and its colonized moon, Anarres. The people of Annares are anarcho-syndicalist dissenters from one of the countries of Urras, having colonized the moon two centuries previous. They are largely perceived as naive dreamers by the various political factions and countries of their planet of origin, which is belied by the incredibly harsh conditions on Anarres. You have to be tough to survive life on the colonized moon.

In chapters that shift back and forth in time, the novel follows Shevek through his childhood and education on Anarres. When he runs afoul of political dogma in his scientific work on Anarres, Shevek travels to a university on Urras to further his study. His experience of the traditionalist, capitalist society he encounters on Urras is tragicomic at times—there’s a depiction of a faculty party where Shevek is several leagues out of his depth which would not be out of place in a campus novel. Although the university on Urras allows him to complete his General Temporal Theory (which provides the theoretical framework for the invention of the ansible) the political structure and society of Urras is repellent to Shevek. The novel is a story in ironies and dialectics: the scientist who could only be produced by this society, but could only complete his life’s work in that. The interactions between the various countries, societies, factions, and parties of the populations on Urras and Anarres are a direct refutation of the skiffy trope of The Planet of Hats, where fictional worlds resolve to the most simplistic economies; I find it difficult to encapsulate all the political maneuvering in the story of Shevek’s great invention. But The Dispossessed is also the story of a single person. Like The Left Hand of Darkness, the focus on the personal grounds a novel of ideas into bedrock.

The Lathe of Heaven

The Lathe of Heaven tells the story of George Orr, a young man who is plagued by what he calls “effective dreams,” or dreams that change the nature of reality itself to conform to the dreamscape. George is the only one who is aware of these changes. He’s remanded to the psychiatrist and sleep researcher William Haber, due to his abuse of drugs to try to stave off the effective dreams. Haber begins tinkering with Orr’s effective dreams, trying to improve reality through his manipulations of Orr’s dreamscape. This results in escalating dystopias. When Haber pushes Orr to dream of a solution to world overpopulation, a plague kills billions. When he tries for a world without racial strife, everyone turns grey, and Orr’s social worker, friend, and sometimes paramour, Heather, who is biracial, ceases to exist. Like a series of wishes in folklore, each effective dream seeks to solve the problem of the last wish, but then creates another.

The Lathe of Heaven is a beautifully written novel, an almost perfect example of Le Guin’s compact and insightful prose. She never much went in for poetic prose or the extended metaphor —her observations tend to be grounded very closely in material culture. The Lathe of Heaven opens with the metaphor of a jellyfish: “Hanging, swaying, pulsing, the most vulnerable and insubstantial creature, it has for its defense the violence and power of the whole ocean, to which it has entrusted its being, its going, and its will.” This image pops up again and again, a metaphor for her conception of the Tao, for the tides of dream, for the eddies of history. (The name of the novel was taken from a line by Taoist writer Chuang Tzu, though, amusingly, Le Guin discovered later that this expression is a mistranslation.) The intensity of the relationships in The Lathe of Heaven—George and Haber and Heather in almost claustrophobic proximity, set against the changing canvass of history—and the beauty of the language Le Guin uses to tell their stories set this novel apart.

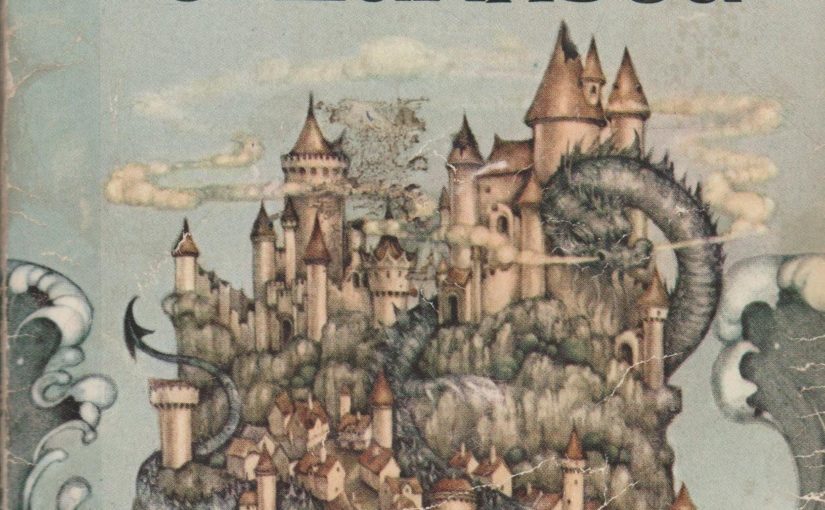

A Wizard of Earthsea / The Tombs of Atuan

I’m going to cheat and place both A Wizard of Earthsea and its sequel, The Tombs of Atuan, as Le Guin’s best. A Wizard of Earthsea is regularly (and rightly) called out as one of Le Guin’s most important and influential novels; less so The Tombs of Atuan. But I feel like, considered together, the two books form a vital dialectic, a duology that is greater than each individual novel. A Wizard of Earthsea tells the story of a boy’s growing up, an almost perfect iteration of the Western fantasy monomyth slash bildugsroman. This sort of story—one of a boy growing into a man—is a mainstay of fantasy literature (sometimes frustratingly so). Le Guin tells it so sharply, with such an important twist, that alone it would be her best.

“The island of Gont, a single mountain that lifts its peak a mile above the storm-racked Northeast Sea, is a land famous for wizards.”

So begins A Wizard of Earthsea, a slender young adult novel with a most common theme: a talented boy’s journey to becoming a great man. The talented boy in this telling is Sparrowhawk, born in obscurity on Gont, an island on a archipelago known for wizards and pirates and not much else. The magic of Earthsea is word-magic, a language of making and unmaking that can be learned by people, but is native to the dragons of the world. (Dragons can lie in this true language; humans can’t.) During his education on Roke Island, Sparrowhawk attempts forbidden magic (like many matriculating heroes, Sparrowhawk is something of an arrogant jerk) which backfires, conjuring a gebbeth, a shadow creature that is tied to Sparrowhawk. The archmage gives up his life to repel the shadow, and Sparrowhawk is scarred and grievously injured.

Nonetheless, Sparrowhawk, whose true name in the language of magic is Ged, eventually receives his wizard’s staff, takes a position as wizard on a neighboring island, and does battle (largely through language) with the dragons of Pendor. These are the events that will make him famous, the things he will be remembered for in song. But the shadow still haunts him, and Ged leaves his posting in order to either find or escape his shadow. At this point, the novel becomes a picaresque, traveling almost haphazardly through the waters and island of the archipelago of Earthsea. In the end, Ged and his dear friend Vetch sail clear off the map, onto shifting near-material sands, and he and his shadow name one another. Like the confrontation with the dragon, Ged’s final conflict with his shadow isn’t one of brute strength or some blinkered concept of “goodness,” but one of balance and equilibrium, of empathy and understanding. I name you; I know you.

Le Guin’s simple tale of matriculation stands out in its simplicity. She packs in a wizard’s mean upbringing, his boarding school days, his exhilarating successes and embarrassing failures, into a novel that never feels rushed, even while it tells a tightly constructed tale. And the twist: Le Guin reveals, after the getting-to-know-yous of Ged’s important life, that he has black skin. In fact, most of the people of the archipelago range from red-brown to blue-black. Early covers elide this important detail; even a miniseries produced in 2004 got it horribly wrong, much to Le Guin’s irritation. Maybe it doesn’t matter what the skin color of fantasy characters is, but if it really doesn’t matter, then why are they always white?

The Tombs of Atuan is set in the Kargish empire, where people indeed have white skin. Though part of the larger archipelago of Earthsea, the Kargs set themselves apart from the Hardic people (who are Ged’s people.) Where the rest of Earthsea hews to something like a Taoist appreciation of balance in magic, the Kargs are beholden to the Old Powers. Their society is based on a theocracy of squabbling god-kings. Tenar is taken as a young child to be a priestess of one of these Old Powers, in a cloister built on a labyrinth. She’s referred to as Arha, the Eaten One, and is raised in a suffocating convent peopled by women and eunuchs as a god-child (or goddess-child), the reincarnation of the previous Eaten One. Her experience is one of frustrating enclosure, hemmed in by the parameters of duty and expectation, in addition the the physical constraints of her isolated cloister; there’s literally nowhere to go.

She finds freedom, ironically, in exploring the undertomb, the underground labyrinth, a place only she, as Arha, may enter. It is there she finds Sparrowhawk, the archmage Ged, injured and diminished by the effects of the Old Powers. He’s come to retrieve (or steal) an artifact, but he’s failed and failing. Ged’s intrusion into Arha’s structured and bounded life is a shock; he puts everything about her life into question. They enact a series of conversations in the dark of the undertomb, conversations which feel dangerous to Arha.

While A Wizard of Earthsea gives us an almost comforting coming of age story, The Tombs of Atuan sails right off the map, giving us a monomyth scrambled by the vital and necessary aspects of race and gender. Ged is a surprise to Arha; The Tombs of Atuan is a surprise to the reader. A Wizard of Earthsea and The Tombs of Atuan function as a dialectic, as call and response about gender and power, race and culture. They are beautiful, careful books that tell essential stories in Le Guin’s quick, clear prose, and are filled with the themes most vital to her storytelling. They are everything I love best about the writer I love best.

What is your favorite Ursula K. Le Guin novel?