History is weird, right? I mean, our lives and actions pass through this lens of the now, and then are magically transmuted into then, and rendered both complete and imperfect, all by the passage of immaterial time. Complete because it is over and done; imperfect because it’s not-whole, artefacted, metonymous. One of the oddest sensations I can think of is that overpowering feeling of “No, no, this can’t have happened this way; there must be a way of wishing this away,” when I screw something up. Not just kind of screw up, but screw up in that soul-rending way; the regretful way. Yeah, yeah, I know one shouldn’t wallow in regret, and we learn best from our mistakes, and all that cheerful shit, but sometimes being confronted by the sheer thickness of my own skull can be mortifying enough to wish for time travel. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, may you live long enough to plumb the depths of your own thoughtlessness. I mean this in the best possible way.

My grandfather suffered from senior dementia in the last decade of his life, and we first knew something was wrong when he began telling stories about WWII. He was doctor attached to the Marine Raiders in the South Pacific, and due to his temperament and generation, he never much talked about the things he saw during the war. But before the stories vanished into the cruel forgetting of senility, they shook loose and came pouring out of him. We learned about several brushes with death, the insanity and shelling, the bad times and panic. We also learned about good things: the Australian doctor he befriended; the times he spent at the other doctor’s farm which reminded him of the Iowa farming community where he was raised. He said he loved Australia so much that he would have moved the family there after the war, had his elderly father not been living and in need of care. I never knew this, and it kind of blew my mind: how many times he nearly died; how if the wheel had been spun differently, my grandma would have been a widow with a war baby, or if he had lived and they had moved, there’d be an Australian not-Ceridwen, the daughter of my father but not my mother.

I know, I know, this sort of musing is somewhere near the pinnacle of self-involvement, a personal strong anthropic principle. But I think this sort of thinking can be found in the unconscious assumptions that underpin all manner of historiographies. Is history long or short? Does it cycle, pulse, or is it flat like ticker tape? Are we at the end of days, or the beginning, or is that the wrong answer to the wrong questions? I’m fascinated by how many religions have a get-me-out-of-history lesson as their central idea: the Hindus and Buddhists are both trying to get out of the cycle of rebirth, but they disagree as to methods; the eschatological Christians viewing the world as a giant Rube-Goldberg-like device: if we can just move these people here and those people there, then Christ will return and end history. What’s up with this? I mean, sure, life sucks, except for when it’s insanely cool. Why do we make historical suicide sacred? But I’ve pined for the screw-up changing time-machine, so I guess I get it.

So, wait, what the heck am I talking about? I haven’t even started talking about The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson. I’m so completely suffused with love and admiration for this book that I feel and dreamy and half-lit. (I mean that both in the inebriated sense and the illuminated sense.) Several people recommended this book to me after I freaked out about how awesome plague narratives were. While this book peripherally deals with the Black Plague, in that the story is a thought experiment that resets history when the 14th Century plague wipes out almost all of the population of Europe, instead of only (only) the 30-50% most historians estimate. Did you know that the population of Europe, didn’t rebound to pre-plague levels until well into the 1800s? This is in the real world, not the world of the book. Although, man, I feel mind-blown enough to see that both histories are constructed, our internalized values of historiography subtly or not so subtly influencing what we accept as real, as fact, or as important. Do you know what I mean?

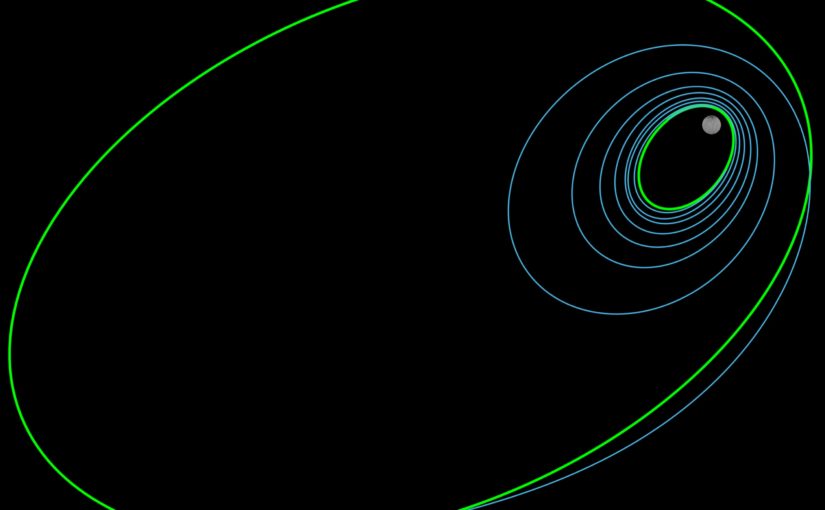

I’ve been reading a fair amount of alternate history, authors re-spinning the wheel to different results: what if? what if? I haven’t quite figured out what all this messing with history is about in contemporary lit, but I bet it’s related to magical realism in some way. Magical realism has often re-told personal, familial, and national histories with the metaphors made manifest; the alternate history folks seem to be doing something similar, sort of. I haven’t figured it out yet. (Hey, let me know if you have any ideas.) Sometimes this spinning is comic, sometimes an excuse for some ass-kicking. How do events inform ideas? If there was no European history, it if bled out into ruins and bleached bones, who would Galileo be? Are we going to go down the ugly road of European superiority, and claim that medicine, technology, electricity, modernity, all the shit by which we measure progress, could only be developed by Christians/Europeans? Spin the wheel again: who makes contact with the New World?

So, okay, this sounds super boring I bet. This sounds like a droning history class. Then the so-and-sos did this, then they did that. This is not how this book is. It’s grounded in character, written in really lovely language, moving and real and determined not to fall for the easy answers. It’s a frame narrative, using the form that Boccaccio developed in the 14th C to tell his own story of plague and history: the Decameron. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered this particular frame before, which is kind of interesting, because once you say it out loud, it seems too obvious: it follows the same collection of souls who are reincarnated together in the 700 hundred years since the plague.

Now, don’t get me wrong, the whole concept of reincarnation makes me itchy. I mean, gah, how can be be understood to be ourselves when we’re someone else? Also, I hate the whole idea that we’re here to “learn something” in each life, plunked into a hierarchy of being that strikes me as insanely arbitrary. No, strike that, arbitrary would be better. Men above women; human above animal; the rich above the poor. But, don’t listen to me. Pretty much the Buddha has already articulated all these ideas to better and more poetic effect. This is the way I would put it: fuck your dharma. (That’s one for embroidering on a pillow, I tell you what.) Dharma is playing the shitty hand you’ve been dealt with a smile, because them’s the rules. And what bastard made those rules? Don’t ask! Does a dog have Buddha nature? Well, you get to find out. (Or like the character in the book who has my same problem with dharma: tiger nature.)

That’s why this book is so awesome: it is discomforted by its own frame narrative. “Oh Gods, I’m so sorry,” it says, as it reincarnates an African eunuch into a Hawaiian girl. There are no ridiculous birthmarks that endure from incarnation to incarnation; the names don’t start with the same letter; none of that cheating literary bullshit. Robinson rolls the threads of continuity between one character and the next using, and I know this is avant garde, compelling characterization and culturally specific signifiers. Hard to believe, I know. There’s other awesomeness as well: a sensitivity to women’s history, poetry written for the novel that Robinson need not be embarrassed by, unlike many novelists who dabble in poetry, and remarkable restraint when it comes to exposition.

I’ll complain a bit, just to let you know I haven’t been paid off or something: the section that deals with the peoples of the New World is totally weak. I was kind of obsessed with the history of Native America for a while, and one of the reasons we have this idea of indigenous Americans chilling in the empty forest passing the peace pipe around is that Old World diseases wiped out as much as 90% of the population of North America before the people of the interior even knew the anglos were coming. Talk about your plague narratives. There was enormous upheaval going on, before whitey showed up to pass around beads and smallpox blankets, and the groups that we like to think of as static from time immemorial were either the remnants of larger groups who synthesized based on similar languages, like the Catawba, or wholly remade by the introduction of new technologies, like the Lakota/Dakota/Sioux. But whatever, I have an embarrassing lack of knowledge about the histories of the Muslim and Chinese worlds, so I’ll let Robinson slide on his rosy portrait of the decimated and traumatized cultures that peopled this fair continent in the century after Contact. But measles lacks ideology; I don’t care who passed it who the New World first.

I’m trying to figure out how to wrap up; a regular problem for me. I’m no good at plot, as I’ve been told before. Maybe because of this, I like when novels are open-ended. There’s nothing wrong with a puzzle-box: the plots that snick and fold into the origami of meaning. But novelists that capture the zig-zag-whatever of the way my life is actually lived, without being boring or lazy, are often my favorites. So there’s this, from about halfway through the novel, when the reincarnated group, the jati, have just been cut down uselessly by an outbreak of plague. They sit, huddled and demoralized, waiting for their next incarnations:

“Looking back down the vale of the ages at the endless recurrence of their reincarnation, before they were forced to drink their vial of forgetting and all became obscure to them again, they could see no pattern at all to their efforts; if the gods had a plan, or even a set of procedures, if the long train of transmigrations was supposed to add up to anything, if it was not just mindless repetition, time itself nothing but a succession of chaoses, no one could discern it; and the story of their transmigrations, rather than being a narrative without death, as the first experiences of reincarnation perhaps seemed to suggest, had become a veritable charnel house. Why read on? Why pick up their book from the far wall where it had been thrown away in disgust and pain, and read on? Why submit to such cruelty, such bad karma, such bad plotting?

The reason is simple: these things happened. They happened countless times, just like this. The oceans are salt with our tears. No one can deny that these things happened.”

Kim Stanley Robinson, Years of Rice and Salt

I can’t deny it, mired in my own chaoses, subject to the bad plotting of my own life and unrelenting happenstance. I happen, and I continue to happen in this seemingly random way; a way that occasionally, just occasionally points to greater meaning even while it dissolves on closer inspection. I’m not one for big philosophies; I don’t have an overarching theory of history and the world that can account for our cosmic obscurity balanced against individual self-importance. Neither does Robinson, bless his soul.